Early Girls Track and Field

By ROBERT PRUTER

The first year that the Illinois High School Association began sponsoring interscholastic track competition for girls was 1973, and the sport joined basketball and bowling (both added in 1973), plus tennis (added 1972) to the menu of state championship competition. Southeast (Springfield) won the first championship. Girls had been competing in park district and Amateur Athletic Union events for decades, but the addition of high school competition brought many more girls into the sport of track and field. Girls across the state flocked to the IHSA program and the sport prospered. But the girls of the state today owe a great deal to the girl pioneers of high school track and field, who had to overcome social and institutional barriers to compete.

Track and field for girls in Illinois has for most of its history has not been sponsored as an interscholastic activity. The following could be considered as a history of girls' interscholastic track and field on the margins. While direct girl to girl competition involving school colors was virtually nonexistence during the previous century, high school girls were in fact leaping, hurdling, racing, and throwing just like the boys. During the school week in the high schools, the track and field contests were all intramural, but just as often on the weekends the girls were competing against one another in park district contests, in "exhibitions" at boys' interscholastic contests, and in world class amateur meets. Often the girls wore their school colors at these contests, and their high school newspapers and yearbooks wrote them up as star representatives of their schools.

The first stirrings of high school girl track activity came from a couple of annual field meets at two Chicago schools, Lake View and Phillips. In 1900, Lake View High on the north side began experimenting with girls' track and field contests when it started up a field day. At most high schools field days were a fading institution, but at Lake View one particular teacher, Emil Groener, conceived the field day and promoted it as a huge spectacle-with track events for both boys and girls, mass calisthenics drills, and grade school relay races. The field day was held in the last week or May or first week of June. In the first year of the field day, the coverage by the Chicago Tribune finding girls' participation to be such a novelty focused on the girls, often in a condescending manner. Reporting on the 25-yard dash for the first year girls, the paper wrote, "At the start they were bunched, but some friend of Aleca Bosselman cried out, 'A mouse,' and Aleca doubled her pace and won in a walk." The girls were all dressed in navy blue bloomers with white Tam O'Shanter hats-bloomers were chosen by vote of the students-and made a striking image in the mass drill. By 1902 the field meet was attracting 5,000 spectators, described by the Chicago Tribune as "friends and parents of the pupils." Boys participated in the 100-, 220-, and 440-yard dashes, the half-mile run, and mile run. Girls participated in the 25-, 50-, and 100-yard dashes, and high jump. Races were conducted in each event for contestants in each of the four classes.

The spectacle of the field day was provided by the colorful mass drill, which was performed by 450 students. In the gymnastic drills, girl participants, dressed in blue gymnasium suits and white capes, twirled hoops decked with ribbons and held American flags with their hands raised above their heads. The boys, dressed in red tracksuits and red hats, conducted calisthenics exercises with ornamented poles.

The following year, the Chicago Tribune, again ran a feature on the Lake View field day, but finding the participation of the girls so newsworthy, focused virtually all its story on the girls. Of the six photos run by the paper, five showed female participants. Events for the girls were 25, 50, and 100-yard dashes, a running high jump, and running broad jump. There were two mass drill events for the girls-a sash drill and a hoop drill. A basketball game between a picked team of girls and an alumni squad was also a part of the festivities. The article devoted one small paragraph to the boys' events. Lake View ensured that the field day offered sufficient spectacle, by opening the festivities with a mass march onto the field, followed by the mass drills, in the following order-the sash drill by the first and second year girls, the iron wand drill by the boys, the hoop drill by the third and fourth year girls, and the finale mass exercise involving 600 students which the Tribune described as a "combination sash, wand, and hoop drill."

Lake View's last field day was held in 1906. The school was not only a pioneer in intramural track and field work for girls, the school also conducted an annual track and field contest with McKinley High up to at least 1906, but no reports of this annual event has surfaced. The reason that the field day for girls was considered such a novelty by the sports writers is that the prevailing ethos of the day frowned on vigorous athletic activity by girls and women, and especially on competition in front of spectators. Many physical educators of the day urged "moderation" with regard to female sports to reduce the level of physical stress in the activities and to eliminate any public competition. The Lake View field days appeared to be a prime candidate for the imposition of such "moderation."

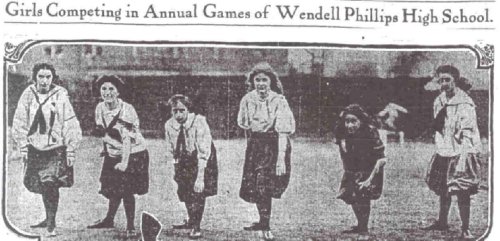

Phillips High also conducted an outdoor field day, from 1905 to 1911, which brought hundreds of boys and girls together to participate in mass calisthenics and track and field events. Besides the decorous calisthenics, these "new athletic girls" competed in dashes and hurdle races, beanbag throws, and broad and high jumps. The Chicago Tribune, as with the Lake View field day, gave extensive coverage to the events, illustrating them with large photos of the girls hurdling, tossing, and jumping. By 1911, the last year of the field day, Phillips High had eliminated the jumping contests and added ethnic dancing. Moderation had set in. A Chicago Tribune sports writer lauded the Phillips field day concept, saying, "instead of being confined to a few of the physical experts the contests were participated in by hundreds, both boys and girls. This is the proper conception of athletics for scholars, whether in the schools or the colleges. Other institutions might well follow Wendell Phillips' example." This was truly a voice shouting in the wilderness, but his points would be echoed by women physical educators in their movement to suppress interscholastic sports for girls.

Although the field days of Lake View and Phillips soon became a memory, they represent a laudable early example of Chicago area educators who saw no reason to exclude their young girl charges from track and field competition, even of the intramural variety.

After the last Phillips field day in 1911, Chicago high schools were fairly barren of girls' track and field competition for a number of years. In the early 1920s, some Chicago schools, notably Hyde Park and Lake View, organized intramural track and field competition, Hyde Park with an intramural track team and Lake View with a revival of its field day. The sport had been banned as an interscholastic activity throughout the state for some years, but by this time the city's high school girls were beginning to find many opportunities to compete outside their schools. The Chicago Park District, private clubs, Turners organizations, and church leagues all sponsored competition for women and girls. In 1923, the Central AAU opened its annual indoor meet to women's competition, the same year that the National AAU introduced a national women's championship meet. At the Central AAU meet, fifty women and girls participated in the high jump and 50-yard dash. Among the competitors was an extraordinary high school runner, Helen Filkey, who while a student at Lake View was competing for the Cornell Square park district team. The following year, the Central AAU lengthened the dash to 70-yards. Among the competitors in the event was Nellie Todd, who ran as a representative of Lucy Flower High, an all-female public vocational school on the West Side. Another girl from Lake View High, Norma Zilk, ran as "unattached." Interestingly, at the Chicago High School League indoor games a couple of weeks earlier, both girls competed in "special events," whereby Todd reputedly set an American record in the 60-yard low hurdles and Zilk set the record for the 60-yard dash. Todd would eventually become an AAU national champion and world record-holder in the broad jump.

In 1925, the Central AAU expanded its events for women to include a 70-yard hurdles and a 1/3 mile relay, and a team of Senn high school girls competed in the relay and the individual running events under the school name. In the mid-1920s, Chicago high school girls would occasionally list their high school as their affiliation when competing in outside meets, and sometimes they would meet head to head, as when freshman Helen Filkey, representing Lake View, raced against Nellie Todd, representing Lucy Flower, in a meet in 1924. In the Bradley Interscholastic of 1924, meet officials presented four "exhibition" events involving high school-age girls, but without listing their school affiliation. For example, in the 60-yard sprint, Dorothy Smith (Senn) beat Marie Teichman (Lake View) to set a new world's record, and in the 70-yard dash beat Teichman to tie the world's record. Her achievements were worthy of mention in Time magazine, which reported "Dorothy Smith...bedecked in bewitching bloomers, pattered the ground with graceful feet 60 whole yards in 7.7 second, bettering her previous mark by point three seconds. She also ran 70 yards in 8.8 seconds and thus tied the world's record." In the Bradley games of 1925, Helen Filkey (now of Senn) and Marie Teichman (Lake View), again without listing school affiliation, raced against each in an 80-yard run in which Filkey set a new world record. In an indoor Illinois Athletic Club meet in 1926, Filkey ran against two other high school girls, Nellie Todd and schoolmate Dorothy Smith, in the 70-yard dash, setting a world record. No school, however, was listed on their jerseys in what could be considered an interscholastic contest. The girls were coming close to interscholastic competition, but not quite, as no secondary school authorities were sponsoring the contests.

All through the 1920s, the local newspapers gave coverage to the girl track and field contestants without condescending and without qualification, and marveling in the records they set. Chicago was alive with great high school girl track and field talent. Readers of the local newspapers would learn about star high school runners such as Helen Filkey, Norma Zilk, Marie Teichman, and Nellie Todd, and in their schools their fellow students would learn about their achievements in the school newspapers and yearbooks. The Lake View High publication, Red & White, profiled freshman Helen Filkey in its April 1924 issue, who by this time was already setting national records in track. The publication next profiled Marie Teichman in its December 1924 issue, and in the story related that she and fellow Lake View students Norma Zilk and Helen Filkey traveled to Canada and Detroit to compete in meets.

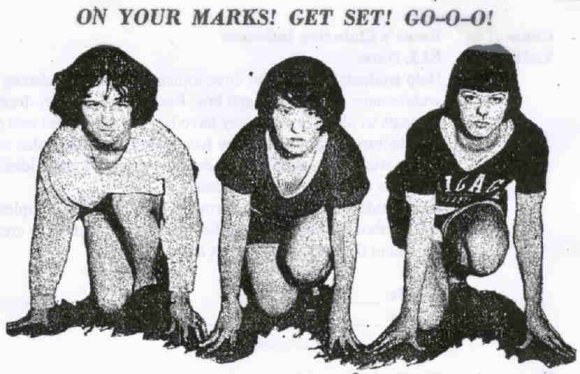

The next year Helen Filkey transferred to Senn, and there became the school's biggest celebrity. She quickly became the best-known female athlete in Chicago in the mid-1920s. Almost weekly every spring and summer the Chicago newspapers--all which featured a photo page then--would show photos of Helen Filkey, running, hurdling, or jumping to yet another new national or world record. The Chicago Tribune in one issue ran a celebrity-style photo of her under the hood of a car, showing her at Senn High learning automobile repair. Filkey while in high school attained national titles in dashes, jumps, and hurdles events, holding AAU title in the latter from 1923 through 1929. In 1926, Filkey--by this time a national champion and record holder in the broad jump, the 100 yard dash and 60-yard hurdles--was presented in a newspaper photo with two high school classmate runners. All three girls were aligned in a starting position, and the caption read "Helen Filkey of Senn High, America's premier girl athlete, is determined that her school will not be without representation after she graduates. This shows her with two girls that promise to star on the track this season." The two girls, Dorothy Smith and Dorothy McWilliams, were already notable runners, and with Filkey were competing for the Midwest Athletic Club.

At Senn, Filkey competed in intramurals, in swimming and track, and was twice elected president of the Senn GAA. She also assisted the faculty coach in training the girls' track team. In her senior yearbook photo of 1928, this national figure's achievements in sports were merely listed as "intramural sports." On a separate page in the yearbook, however, Senn ran a photo of "Our Helen Filkey," and surrounded it with an essay on the progress of the woman athlete, an ironic turn given that during Filkey's stay at Senn the status of women athletics had regressed. School authorities in 1927 had banned all high school interscholastic activity for girls, and had barred all high school girls from running in their high school colors in outside meets. After graduation, at the Olympic Trials, Filkey unfortunately fell in the qualifying 100-meter race, and although she won the 60-yard hurdles, the Olympic Games at that time did not have a hurdles race for women. Thus, one of America's great female track and field athletes could never call herself an Olympian. Filkey generated such long-lasting fame that when she died at the age of 92 in 2000 both Chicago dailies published large and laudatory obituaries.

Filkey's compatriots would win many titles and honors during the 1920s. Norma Zilk would win many Central AAU titles and set a national record in the 100-yard dash and world records in the 80-yard dash and the 220-yard run. Nellie Todd, besides her Central AAU titles, would go on to win national AAU titles in 1926, 1929, and 1932, and race on the AAU national champion 440 yard relay team. She would also set a national record in 70-yard hurdles and a world mark in the broad jump.

The Chicago high school girl track and field athletes were not coached by their high school gym instructors for the most part, but by Tom Eck, the long distance coach at the University of Chicago but who had taken a special interest in developing female track and field talent from the Chicago high schools. During 1925-26 most of the top high school competitors were affiliated with the Midwest Athletic Association, but by 1927 most would be training at and competing for the Illinois Women's Athletic Club (IWAC).

In 1927, Chicago public high schools began joining the Illinois High School Athletic Association, which had strict rules against girls competing in outside competition. Senn High, which had for several years, had seen its girls compete in track and swimming meets under Senn colors, made note of changes in the rules in its 1927 yearbook, which banned high school girls from competing under their school name. The yearbook editor boasted of four Senn girls winning a relay at an AAU meet at the Broadway Armory. The girls presented to the school a "wonderful trophy," apparently feeling that they ran for the school, even though they could not wear the school colors.

The Chicago schools would continue to produce outstanding track and field athletes. Nan Gindele, for example, who would win fifth place in the 1932 Olympics with the javelin throw, went to Schurz High, when the school did not have an intramural track team. On the other hand, she served as captain on the school's volleyball, basketball, and field hockey teams, and upon her graduation in 1929 was voted, not surprisingly, the "most athletic." Besides her Olympic glory, she won the national AAU javelin title in 1933, and took the AAU basketball throw three times.

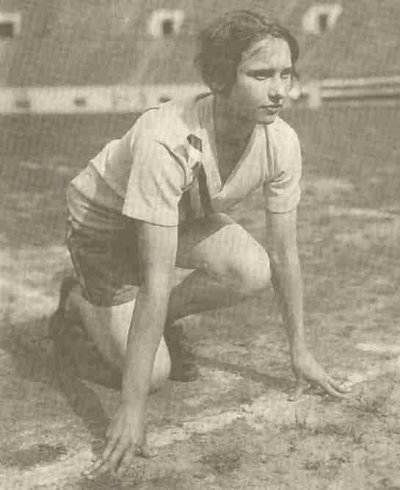

The experience of many of the Olympians that came out of Chicago areas schools at this time probably replicated Nan Gindele's experience. America's first Olympic Games track gold medal winner, Betty Robinson, who won the 100 meters at the 1928 Games, came from Thornton High. She also won silver in the 400-meter relay. Robinson was discovered by her biology teacher, running for the train that went from her home in Riverdale to school in Harvey. He trained her until she received further training in the amateur teams in Chicago. She went on to win several more national titles, but after winning gold in the 400-meter relay in the 1936 Olympics she retired from competition. Tidye Pickett, who made the 1932 and 1936 American Olympic teams, received her training in the Chicago Board of Education playground program, but she was recognized as such an outstanding athlete at Englewood High she served as the school's correspondent to the Chicago Defender, relaying news of various athletic achievements of her fellow Englewood students to the nationally distributed black newspaper. Typically, the papers of the day invariably referred to her race, such as the Chicago Tribune report of the 1934 Central AAU meet, "Tidye Pickett, a Negress from Englewood High, was the individual star..." She won the national AAU 50 meter hurdles title in 1936.

Olympic 1932 and 1936 winner Annette Rogers was a product of the great track and field tradition for girls established at Senn High, but by the time she was attending the school in the early 1930s the encouragement by the school was not as big as in Helen Filkey's day. She began very early in track and field when she was in grade school and began participating in a local Chicago Board of Education playground program. She next graduated to the prestigious IWAC team. Rogers won many national AAU titles in 100-yard, 200-meter, high jump, and relay events. Evelyn Ferrara and Evelyne Ruth Hall were two other Olympians who came out the Chicago amateur ranks, but their high schools have not been determined.

As was true of Helen Filkey, not all of Chicago area top female track and field athletes were destined to become Olympians. A top competitor of the early 1930s was Mary Terwilliger of DeKalb High. She found that at high school she was so fast that in intramural competition no girls even came close to her. She searched for better competition in Chicago and in 1932 entered her first race in a novice competition sponsored by the IWAC. She did so well, that the IWAC asked her to become a member. The same year as a member of the IWAC 400-meter relay team she help set a new American record. In the 1932 and 1936 Olympic trials, Terwilliger just missed qualifying by inches in her races, but she shared national AAU first place honors in the 440yard/400meter relay three times. Lindblom High, on Chicago's south side, during the 1920s and 1930s had a vigorous GAA program for girls, and one of the program's top female athletes was Genevieve Valvoda, who in competing for the park district, won the national tile in the broad jump in 1933.

While there was not a single meet sponsored by the Chicago Public High School League during the 1920s and 1930s, the grammar schools would conduct an annual track and field meet for both boys and girls. The shame was that once the girls entered high school, the interschool competition halted. But there was a slight glimmering of interscholastic competition during the decade, which was greatly overshadowed by the girls' vigorous participation in the park district and club programs, where they routinely set national and international records in their events. The occasional "Lake View," "Senn," or "Lucy Flower" on their jerseys while competing in these outside meets pointed to the much great possibilities decades later, when thousands of Illinois girls would compete annually and all proudly wearing their school colors while competing in dual, league, invitational, regional, sectional, and state meets.

Girls track meet at Phillips High School (Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1909)

Betty Robinson of Thornton Twp. High School

Senn girls track stars, left to right: Dorothy McWilliams, Dorothy Smith, and

Helen Filkey

(Chicago Tribune, Feb. 24, 1926)

Norma Zilk (Chicago Tribune, Jan. 31, 1928)

Published with permission. All rights are reserved by the author.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Illinois High School Association.