Chicago Public Schools Make Their Mark in Swimming: Lane Tech and DuSable in the 1930s and 1940s

By ROBERT PRUTER

Chicago Public League schools have been a negligible factor in the Illinois state swimming meet in the past several decades. At one time, however, in the first two decades of the state meet, the Chicago schools were highly competitive in the meet, and one school, Lane Tech, dominated the meet, winning nine state titles in a ten-year period from 1938 through 1947. This is a story of two of the Public League's programs during the 1930s and 1940s, that of Lane Tech on the city's north side and that of DuSable High on the city's south side. One school was overwhelming white in its student population and the other was virtually all-black in its student body, but what both schools had in common was superlative swim programs, led by top-notch coaches, and which brought fame and glory to their high schools. The Lane Tech swimming team was the perennial champion in the Public League, but DuSable was sometimes a challenger.

High school swimming in Illinois was undergoing a dramatic shift during the late 1920s and early 1930s. The private clubs and universities that had sponsored such sports as basketball, track and field, and swimming were being forced out by state high school associations. One way that this affected swimming was that prior to the early 1930s most of the high school swimming talent had been developed in private clubs, such as the Illinois Athletic Club and the Lake Shore Athletic Club, but now the high schools were developing the swim talent through coaches on their athletic department staffs. Lane Tech was led by the legendary John Newman, but DuSable had a coach who while never achieving the fame as Newman was probably equally dedicated and equally talented in producing swim talent, William Mackie.

Lane Tech and DuSable Develop Competitive Programs

Lane Tech began to emerge as a swimming power in the fall of 1934, after it moved from its old location at Sedgwick and Division to a new larger facility at Addison and Belmont. The old building had no swimming pool, and the team had been by coached by a gymnastics instructor, E. C. Klafs. The new building gave the team the finest 75-foot pool in the Chicago high schools. Besides the new swim facilities, the team got a new coach, John Newman, who had been the assistant to the old coach. He was born around 1895, and went to high school at St. Ignatius, and college at St. Viator's College. Upon graduation Newman entered the Viatorian religious order, and began teaching and coaching at St. Viator's in 1918. Said a former swimmer of his, Jack Masters, who competed at Lane 1945-48, "He was a football player. He never swam in high school or college. He first coached swimming at the old Jewish Peoples Institute (JPI). He learned a lot about coaching swimming there. He was observant and picked up a lot of things." From 1921 to 1929 Newman coached at the Jewish Peoples Institute, where he helped develop a top swimmer in Freda Silbert, whom he married around 1929. He most notably developed the great swimmer and Olympian Al Schwartz, who won many titles for Marshall High (but most of his training took place in a private club). Newman's move from the Jewish Peoples Institute to Lane Tech in 1929 epitomized the migration of swim coaching talent from the private clubs to the high schools.

Lane was the technical school for the entire North Side, and that was the school's boundaries, and in the early 1930s the school was attracting from 8,000 to 8,500 students, all male. By the 1940s the numbers were around 7,000 to 7,500 students. Coach John Newman had a lot of numbers to work with.

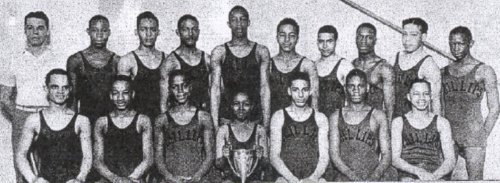

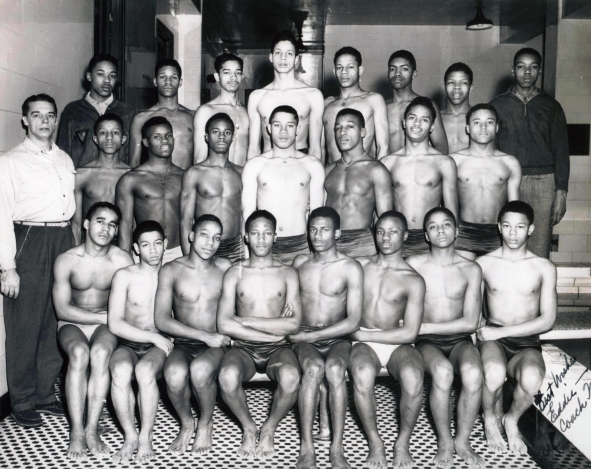

DuSable, 1936

DuSable High opened its doors in the fall of 1935, at 4934 S. Wabash, in the heart of the black South Side. The school during its first year was known as New Phillips, because the Chicago Board of Education had plans to close Wendell Phillips, which had been the principal secondary school serving the black South Side community. That did not happen, and in the late spring of 1936 the school adopted the name DuSable, after the first settler of Chicago, Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, a French fur trader whose mother was a Haitian slave.

The old Phillips High, from which most of the students of DuSable were drawn, did not have a swimming pool, which was also true of many other Chicago secondary schools. DuSable High was built with a swimming pool, and its athletic department immediately instituted an ambitious swimming program under Coach William T. Mackie. He was born September 16, 1907, attended De La Salle Institute, and swam competitively for the Hyde Park YMCA. He received his higher education at the YMCA’s George Williams College and Northwestern University.

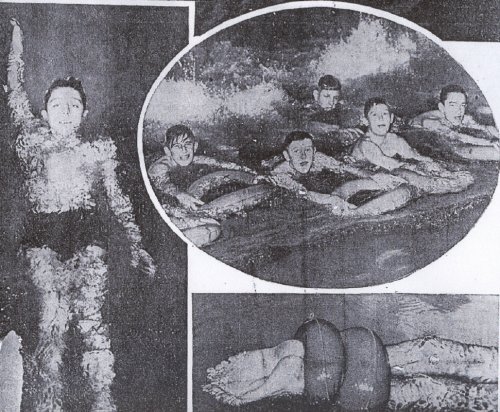

Mackie introduced a 10-mile swimming marathon. In this program each student swam so many lengths of the 60-foot pool every day until they reached 9 ¾ miles. Then in the last quarter mile they would compete in a race for their positions on the team. Graduates of the 10-mile marathon who finished first, second, or third would use that achievement to try out as life guards for the Chicago Park District to work at swimming venues in the black community—notably the Washington Park pool, the Wabash Avenue YMCA, and the 31st Street Beach, on Lake Michigan. The Chicago Defender explained the purpose of the marathon thusly: "Coach Mackie uses this marathon to get his swimmers and life guards in condition and to encourage boys to swim more distance." By 1941, the marathon competition was attracting 70 competitors. The Defender reported that "more than half" would finish the marathon requirement.

The 10-mile marathon program instituted by Coach Mackie helped immensely to build a competitive swim team at the school, no doubt what Mackie intended. The school fielded a swimming team for the school's inaugural 1935-36 school year. Today all athletic teams at DuSable are called the Panthers, but the swim team in the 1930s adopted the appropriately named Sea Horses. The school's competition in its first year was with non-school teams, namely the Wabash YMCA and the Boys Club. No doubt a racial issue was involved, as many white high school swim teams shunned competition with a black school.

In context, black achievement in swimming was certainly not unique at this time. Elsewhere on the interscholastic level, the segregated schools of Baltimore and Washington, D.C., had been competing in an annual meet for the South Atlantic High School Athletic Conference since 1929. Many of the Negro colleges had strong swimming programs, and beginning in 1948, the Colored Intercollegiate Athletic Association began conducting an annual tournament that drew Negro colleges in the East and in the border states. They drew their swimmers both from the DuSable swim program and from the black high schools in D.C. and Maryland.

DuSable's success in swimming began with an undefeated dual meet season, beginning a streak of 53 dual-meet victories that lasted until 1943, behind such notable swimmers as Wesley Ward, Fred Lyda, and Jack Hall. The Chicago Defender started giving DuSable High headlines in March of 1940 when the school's dual-meet string reached 26 straight. The string then became a recurring story in the paper. While obviously a laudable achievement, the string was less than the readers of the Defender were led to believe. DuSable never had dual meet competition during the streak with any of the top teams in Chicago or suburbs, namely Lane Tech and Crane Tech in Chicago, and Maine Township and New Trier Township in the suburbs. DuSable was generally the only black school in Chicago with a swimming team, as Phillips did not always field a team. DuSable faced only two black teams in these years—Phillips and Roosevelt High in Gary. All the other schools that competed against DuSable were essentially white high schools in the city that to their credit overcame prevailing racist views of the day. These included Wells, Farragut, Harrison, and Amundsen.

Lane Tech Emerges as the Dominant Swim Power

Lane Tech by the late 1930s utterly dominated the Chicago Public League twice-yearly league meets, held respectively in December and April of each school year. The 20-yard pool, or short course, competition was held in December and the 25-yard pool, or long course, competition was held in April. Coach Newman failed to win the first three Public League meets he entered. Englewood High and Roosevelt High (with the great Adolph Kiefer) kept Lane Tech from taking its first senior (varsity) title until the spring of 1936. Thereafter, Lane Tech won each Public League meet for nearly twenty more years. Rarely was the school challenged for the title. But one school did, DuSable, but it would take a while. DuSable had a 20-yard pool and Lane Tech had a 25-yard pool, and thus DuSable tended to do better in the fall meet, while Lane Tech did better in the spring meet. Although the Chicago Public Schools had a long swim season, there was not all that much competition, and dual meets were few and far between.

McKinley Olson, who swam for Newman from 1946 to 1949, recalled "We really had basically three meets a year. We had the 20-yard one in December, usually at the University of Chicago. Then we had the state meet, which was usually at New Trier, and that was in February. Then we had the city championship meet in the 25-yard pool in early April. The number of dual meets was not many." Harold Gold, who swam for Newman from 1940 to 1943, said, "I imagine during the season we competed in four or five dual meets. I recall swimming against Wells High, Crane Tech, and Schurz in the city. We also competed against Shoreham up in Milwaukee." Added Olson, "We were so much better than any other team around I can't see that there was much incentive for any team to want to swim against us in a dual meet." On the one occasion that the Lane yearbook reported on dual meets results, in 1945, only three dual meets opponents were listed—Crane Tech, Oak Park, and Proviso, one city and two suburban schools.

The state meet since its inauguration in 1932 had been dominated by Maine Township high school under coach Sam Marsulo. The school had won five out of the first six states meets. In 1937, Lane Tech, which had not won only one point altogether in the five previous state meets, made a significant mark garnering 29 second-place points to Maine's 35 points. Coach Newman was moving his team up. In the first decades of the state meet, the state winners generally operated as dynasties. The Maine dynasty came to an end with the 1937 meet, after Lane Tech won the state meet the following year.

In 1938, Lane came out on top with 44 points, followed by New Trier with 39 points, and Maine with 24 points. The star swimmer of the meet was Lane's great freestyler, Otto Jaretz, who later won several AAU titles and who in 1940 was selected for the American Olympic team for the Games that were cancelled. Lane's yearbook could not control its enthusiasm, claiming that Jaretz was "perhaps the world's greatest swimmer of all time," and that the team was "called the greatest Prep Swimming Team in the nation." Based on comparative times, Lane Tech was named the mythical national champion that year. The 1938 state win launched Lane Tech as the new dynastic power in Illinois swimming. Otto Jaretz would certainly have developed a Hall of Fame career had not World War II intervened. McKinley Olson reported that Adolph Kiefer told him, that Otto "didn't even begin to reach his potential," he was that good.

The Chicago Public League was particularly well served in the 1939 state meet, represented by seven of the 14 schools in the finals and 18 individuals and relays of the 40 point winners. The meet was completely dominated by Lane Tech, which won by a big margin over New Trier, 50 points to 27 points respectively. Even though Otto Jaretz was gone, the team had two other future all-Americans, in freestyler Robert Amundsen and diver Miller Anderson, both assuredly would-be Olympians in 1940. In the Public League competition, Lane continued its string of winning every senior and junior title since the spring of 1936. The yearbook author was prescient when he wrote "It is difficult to foretell when Lane will be beaten. It is safe to say as long as this combination lasts, Lane will always be on top. Only when some school emulates the example in teaching every boy to swim well will the long domination of the Lane swimming teams be threatened."

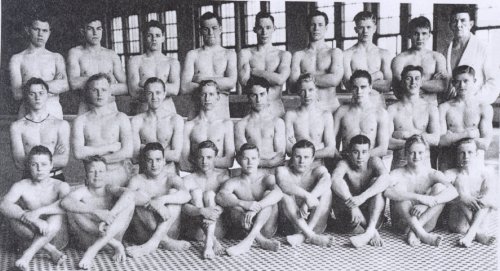

Lane, 1939

The 1940 Lane Tech team was hailed by some observers as "the greatest in the history of high school swimming," according to a February issue that year of the Chicago Tribune. The team's star, Otto Jaretz, was setting national high school and amateur records and had won AAU national titles in 1939 and 1940. He was ineligible to compete in the spring term, however, because he had returned seven weeks late from a Latin American tour the previous summer. In the 1940 state meet, Lane Tech did not fail to impressed, even without Jaretz, and so dominated the competition again that the school swamped second place New Trier by a score of 56 to 36 points. Robert Amundsen scored his customary points, but Miller Anderson had injured his head on the diving board and was unable to compete in the finals, but the school had so many horses his absence made no difference in the outcome. That year saw Lane Tech swimmers establish several national records in individual and relay events. Miller Anderson went onto an illustrious career in diving winning many NCAA and AAU titles and election to the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

Lane Tech continued its domination of state meet competition in 1941, when it bested the second-place team, another Public League school Crane Tech, by a score of 62 points to 23 1/2 points. Crane Tech's high place finish was spearheaded by two freestylers, future Hall of Fame swimmer Walter Ris and Herb Siewert. Lane Tech's team was built on the talents of freestyler Henry Kozlowski, breaststroker Elroy Heidke, and diver Bill McDonald. Koslowski ranks as one of the greatest swimmers every produced by Lane Tech, and went on to became an NCAA champion and world record holder. By the end of the season, the Lane Tech had set several national records, and held seven out of eight state records. The great Roosevelt High swimmer, Adolph Kiefer, held the lone non-Lane Tech record, in the 100-yard backstroke which he set in 1936. Nearly half (19 of 40) of the state finalists were from Chicago Public League schools.

DuSable Emerges as a Swim Power

During the late 1930s, DuSable was garnering only a few points in any of the Public League meets. However, in the December 1939 short course meet, the school managed to take second-place next to Lane Tech. The disparity between Lane Tech and the other schools in the league was immense at this time, as shown by Lane Tech's winning score of 55 points and DuSable's second place mark of 10 points. But the Chicago Defender could brag that DuSable's team was "second only to Lane Tech...and national prep champions." Illinois schools were often tops in the country, and Lane Tech in 1938 was awarded the titular title based on competitive times. This was before the California age group program of the 1950s would produce the talent to overtake Illinois schools.

By 1941, the DuSable swim program was making an impact, with its graduates going to colleges. The Wilson Junior College swim team in April of 1941 took the state's junior college championship, beating out Wright Junior College. The team included three DuSable grads, and one Phillips High grad, described as Phillips one-man swim team.

Racism in the Chicago Public League schools brought the issue of DuSable's swim team competing with other schools to a boil in November 1941. The league's program was based on just the December and April all-schools meets, by which no school was barred. Dual meets among the schools were not conducted in any league schedule—but on an invitational home and away basis. The dual meet competition could be somewhat intermittent. Many of the swimming coaches in the Central Section of the league thus felt the need for more regular competition and decided to form a dual-meet league. These schools included Hyde Park, Englewood, Lindblom, South Shore, Hirsch, and Tilden Tech, as well as the virtually all-black Phillips and DuSable schools.

While some of the coaches of these schools had conducted dual meet competition with DuSable and Phillips, others had not, and were not willing to let Phillips and DuSable into the newly formed league. The Chicago Defender reported, "There have been rumors that although Phillips and DuSable will invite teams to their tanks, few invitations to go to other schools in Chicago will be extended to them...the crux of the whole thing is that these coaches—not the boys—don't want competition against Negro swimmers." One of the most virulent coaches against competition with DuSable and Phillips was ironically the Englewood coach, who apparently was leading an all-white team in a high school that was nearly 60 percent black. A few weeks later, the Chicago Board of Education put an end to the "lily-white swim league," as the Chicago Defender headlined it. This flare-up opened up a window to what DuSable faced each year in fielding its swimming team.

DuSable was highly competitive with the high school teams it did face, however. In February 1942, the Sea Horses bested the Farragut team 45 to 22 in its 42 straight dual-meet victory. In February of 1943, the team beat the Harrison team 42 to 24 for its 53rd straight dual-meet win. A few days after the meet, Coach Mackie was inducted into the Army. There were no more reports of a dual-meet string.

DuSable, 1942

Lane Tech in the War Years

In the 1942 season, Lane Tech began to show some chinks in its armor. The state meet ended up in a tie with newly resurgent New Trier, with each team scoring 40 points. New Trier was directed by veteran Edgar B. Jackson, who assumed coaching duties at the school in 1918. The Lane Tech team got a bunch of points from its two divers, Robert Stone and Bill McDonald, who took 1-2 respectively, and from its freestylers Dick Zachary, Gene Raichel, and Dick Wartena. In the other events, the swimmers suffered from a series of bad breaks according to the school's yearbook. Some of the finishes were so close, that Lane swimmers lost out by a finger. The yearbook said that, "The worst break came in the hundred yard breaststroke. Hal Gold, City Champion, was leading the field and was seven yards away from the finish when he took water and was forced to quit." Gold remembered that mishap well: "I took water, it stopped me cold. I was very depressed afterwards, but Coach Newman put his arm around me and said, 'Things happen, that's all.' He was very good about it. In fact, all my team members were very good about it too."

The 1942 meet featured a future coach, Dave Robertson, who took second in the backstroke for New Trier. He would succeed Jackson as New Trier's coach and build one of the best programs in the nation during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The 1943 state meet was another close affair, with Lane Tech edging out New Trier by a score of 43 to 42. The meet, as it often does, came down to the relays, as both teams were tied at 25 points each. In the 150 medley relay, New Trier beat Lane to jump ahead 35 points to 33 points. But in the 200 freestyle relay, Lane Tech took first, and Oak Park nosed out New Trier for second, giving Lane Tech the meet victory. Among the individual point scorers for the Lane team were Robert Korte, with a first in the 200 freestyle, Harold Gold, with a second in the 100 breaststroke, and Bob Burr, with a first in the 100 backstroke.

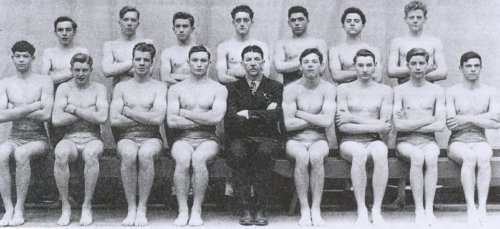

Lane, 1943

Lane Tech's string of six consecutive state championships came to an end in the 1944 meet. New Trier easily bested the Lane Tech team, 70 points to 32 points. New Trier took seven of eight firsts. The lone first place won by Lane Tech was Dick Hennigan's win in the 200 freestyle. New Trier certainly looked as though it was ready to take over as the Illinois meet next dynastic swim power. However, Lane Tech had a few more great years ahead, and was not ready yet to surrender its dynastic hold on the Illinois state meet.

In the 1945 meet, Lane Tech edged out New Trier, by three points, 46 to 43. The reason was Lane Tech had produced yet another great all-American swimmer in junior Bob Gibe, who won both the 50 and 100 freestyle events. While the state meet was tightening up each year, Lane Tech continued its overwhelming dominance in the Public League's annual fall and spring meets, continuing an unbeaten streak that began in the spring of 1936. In the long-course meet in April, Lane Tech took first with 57 points, followed by Steinmetz with 14 points.

The 1946 meet saw Lane Tech return to its state meet dominance, winning the meet over Highland Park, 64 points to 26 points. New Trier took third with a lowly 14 points. Lane Tech took every individual title, except breaststroke which was won by Highland Park's George Hiller. Bob Gibe, now a senior, repeated his double win in the 50 and 100 freestyle events. Lane Tech took second in the two relay events. Gibe went on to become a member of the 1948 Olympic swim team and to win a national title in the AAU meet, in 1949.

The 1947 state meet saw Lane Tech win its last team championship, edging New Trier by the narrowest of margins, 40 to 39 points. Going into the final relay, the 200 freestyle, New Trier was leading the meet 39 points to Lane's 30 points. New Trier had no relay team in the event, but Lane Tech needed first place and its ten points to win the meet. The Indians got the first place when the team of Jack McDonald, Elmer Newell, Bob Schumacher, and Dick Treskow edged Rockford West for the win. Freestyler Holger Stohl two wins in the 50 and 200 freestyle provided 12 crucial points.

The Judge

Lane Tech Training, 1942

What Lane Tech achieved in the previous decade was remarkable, winning nine out of ten state championships, and winning every Public League fall and spring meet. Two major factors that contributed its success were the school's numbers and the school's coach. Each year Newman had the pick of from the 2,000-2,500 freshman boys enrolled in the swimming classes. In a long story on Lane Tech's program in January 1942 in the Chicago Daily News, when Lane Tech enrolled 2,300 freshman boys, Newman explained his coaching philosophy based on his belief that the formative age for development of a swimmer was the 13-14 age group:

To develop a championship swimmer you have to start him on the way as a freshman ...We generally end up with a squad of 36 freshmen swimmer and keep them working out with the junior and senior teams every day. They make a lot of noise, they get in the way, but they get to swim every day of the school year and that is what counts. At the end of every practice session we have a series of competitive sprints and that way each freshman has plenty of races under his belt by the time he moves up on a regular team.

The Chicago Tribune, in 1951, reported, "The secret of Lane's long swimming monopoly is Coach John Newman's ability to develop freshmen candidates. 'Our competitive teams are just a by-product of an athletic program that has 2,377 students enrolled in swimming classes. Our main concern is to make sure all our boys can swim,' Newman declared. Of course, in teaching so many boys to swim Newman is able to spot a youth who shows promise of becoming a future star. By constantly interesting underclassmen in taking up swimming, considered by many schools as a minor sport, Newman is able to keep an ample supply of reserves to take over spots left vacant by graduating stars..."

Dick Zachary (Zakrzewski), who competed for Lane Tech 1941-44 placed the greatest emphasis for his school's success to its size. "The basic thing that helped Coach Newman enormously was that Lane had at this time 6,000 to 7,000 students, all boys. His pool of talent was greater than any other school in Chicago, or Illinois. He recruited the talent from the freshmen swim classes. He of course didn't teach them all. There were other people teaching swimming as well. There were baseball coaches, and football coaches, and tennis coaches. Everybody took a little piece of the heat as far as controlling the swimming pool."

Before he had gone to Lane, Zachary had developed considerable swimming ability growing up in Wisconsin by a lake. In his very first freshman swim class, he was swimming along, when Newman pointed a finger at him and asked him to come out of the pool. He drilled Zachary with a bunch of questions about where and how he learned to swim so well. Zachary continued:

So he immediately on the spot said, 'I've got the fastest 14-year-old boy in the class, and I want you two to swim a length sprint.' And he got the whole class out of the pool. I protested that I had never swum competitively in my life. He said just swim as fast as you can the length of the pool. And I beat my opponent by about a length. He was that kind of guy—very efficient about picking people out for his teams.

Jack Masters said he was also recruited from one of those freshman classes: "The swim coach was smart enough to realize that in these freshmen classes he could pick out those people that he thought could become good swimmers. He would take an immature kid as a freshman, and if he's got a good kick and he looked like he could move pretty good, or could dive, whatever, then he was invited to come after school and practice with the swim team. That's what he did with me."

Harold Gold, who swam for Newman during 1940-43, said:

We called him 'The Judge,' because was always coming down with a decision on us, one way or the other. Coach Newman could develop swimmers out of nothing. He took kids and coached them until they could do well. He just had a perceptive feel about kids. If a kid didn't do well, he didn't cancel them out. He tried me out in the backstroke and the crawl and I just didn't function that way, so when he saw me in the breaststroke, he said, "Hey, that's your stroke!" He saw things in people that they didn't see in themselves. He could bring that out.

The man did not have a deep sense of humor. He was always a serious sort of guy, and he was always serious about how he coached. He would talk to us individually quite a bit and during those times he would discuss our strokes and how we could improve. He was big on timing us on a regular basis, and working us out.

Gold's teammate, Dick Zachary, likewise found Newman to be an impressive individual:

John Newman was a very imposing looking kind of a coach. He had a nicely trimmed moustache and he was obviously well educated, and he was a very intelligent guy. He had the respect of all the kids on the team. He had very strict rules about who goes to where and what they had to do in workouts, and when he says you do this, you did it! I admired him. He was a very nice guy who took a personal interest in the individuals, and had a very good relationship with all his students. Nobody was frightened of him, but they all took him seriously. He made sure everybody did the standard workouts—which were to pull twenty, kick twenty, and swim twenty. At any rate he was very specific about that. Everybody had to do their workouts.

Gold explained the workouts: "We used to swim twenty pull laps with a rubber tube around our feet, just holding our feet together. Then we swim twenty kick laps holding a tube, and then we would swim twenty laps."

Newman was also a brilliant technical swim coach. Masters explained Newman was very good at stroke mechanics, explaining:

You could always tell a Lane Tech swimmer. When he would bring his arm out of the water, the elbow came out first. Then there was the reach on the pull. At the time it was a straight arm pull underneath the water. They don't do that anymore, but at the time it was considered the best way to get your body moving. Newman stuck to his theory about these mechanics of a good arm stroke, and his swimmers as a result excelled at stroke mechanics.

McKinley Olson commented:

Newman was just a wonderful wonderful person, and what made him different from most high school coaches was that he wasn't at all authoritarian. Psychologically he worked with every kid. If a kid wasn't doing too well or needed a little encouragement, he might make the stop watch seem like it was going a little faster. Or if a guy got a bit cocky, he would make it look like he was actually swimming slower than he was.

We had a motto at the school, "The Fastest Man Swims." He might pick the members of the relay team, but any swimmer could challenge anyone on the relay, and if you could beat him then you were on the relay. One of the fastest swimmer when I was there was a heavy smoker, and did all kinds of stuff he wasn't suppose to do, like roller skating. But he not only remained on the team, but competed in the state meet, because of our motto.

Ron Gora related one of Newman's unique recruiting techniques:

He would go out to the lunchroom at Lane, and he would select his people. He would look at them, and then talk them into coming out for the team. It was just by the look. He had a set idea in his mind of what a diver should look like on the board, for instance. So kids that didn't have any kind of knowledge whatsoever on swimming and diving were invited to come out for the team.

John Newman had emerged by this time with a reputation of being one of the finest coaches of swimming talent in the nation, and Chicago private clubs competed for his services. Back in 1941 he was named summer swimming coach at the Tam O' Shanter Country Club, with the aim of producing a team for AAU competition. By 1946, Newman was at the Lake Shore Club, where he was in charge of training women swimmers. He produced such nationally renowned swimmers as Marilee Stepan and Jeanne Wilson.

Lane Tech and DuSable in Postwar Competition

With the absence of Coach William Mackie during the war, DuSable continued to field a team, but without the same rigorous training. The 10-mile marathon program, for instance, was abandoned. In the 1945-46 season, Mackie returned to DuSable. He reinstituted the 10-mile marathon and soon brought the school to even greater prominence in the Chicago swim world. The first two years he lost a few contests, but in the in the 1947-48 season, the school went undefeated in dual meets and won the championship of the Central Section. By this time, the Board of Education had instituted dual-meet leagues to supplement the fall and spring meets. In the fall 1947 meet, Donald Clark became the second DuSable swimmer to ever win an individual title, when he took the Junior breaststroke. The following spring, in the city meet, Eddie Kirk was became the third DuSable individual winner, when he grabbed the 200 freestyle. The Board also introduced a new rule for the annual meets, limiting the number of competitors for each event to two per school. The Lane Tech yearbook opined that the rule "was installed to prevent Lane from completely swamping the other schools."

Meanwhile, in the 1948 state meet, New Trier became the new dynastic swim power in the state meet, beating Lane Tech narrowly 31 to 26 points. Proviso High came in a close third with 25 points, the team spearheaded by future Olympian Jerry Holan in the breaststroke. Lane Tech would have won the meet had not its 150 medley relay team been disqualified. Swimmer Tom Gibe was charged with not making contact with the wall on his turn. The yearbook rendered the verdict as "New Trier beat us out in the state meet when Tom Gibe was disqualified for missing a turn he did not miss." New Trier was now producing top swimmers, notably freestyler Buddy Wallen (son of the great namesake swimmer) and Bob Kivland. This defeat did not end the great teams at Lane Tech. In the program, Coach Newman was training a freshman swimmer by the name Ron Gora, one of the greatest swimmers to come out of Illinois. Gora explained how he entered the program:

I went out to football, and I got injured the very first practice. I got hurt on the knee, and the doctor who was giving me the rehabilitation recommended that I take up swimming—just lounge in the pool, hold on the back of the walls, and stroke my legs up and down, like in the backstroke. As I was always on the wall with my arms on the gutter and my head towards the wall, and lifting up my feet to backstroke position to kick, I developed a real strong kick. Coach Newman saw me and noticed I had some potential. He talked to my Dad about me coming out for swimming, and I joined the team as a backstroker.

In one of the city's junior championships, Gora broke one of the great Adolph Kiefer's backstroke records, but he also broke one of the freestyle records. Kiefer who was actually there officiating at the meet, turned to Gora after he broke his record, joked, "Stay on your stomach!" Gora went during his career to break several national high school records, many city records, and a bunch of state records, competing in backstroke, individual medley, and freestyle. "During my career in high school, college, and as an amateur," said Gora, "I had set some 32 swimming records."

In 1949, Lane Tech was still in the hunt for the state title, but it lost to New Trier by a score of 43 to 32. Again Proviso came in third with 26 points. The star swimmers of the meet were sophomore Ron Gora, who won both the 100 and 200 meter freestyle events, and Proviso's Jerry Holan, who won the breaststroke in record time and led Proviso to the medley relay title. Both swimmers would represent the United States in the 1952 Olympic Games. The Chicago Public League by this time was clearly in decline in terms of generating swim talent. Whereas a decade earlier, seven Public League schools were represented in the finals in 1949 only two made it, Lane Tech and Steinmetz. Whereas in 1939 among 40 finalists, the Public League produced 18 scorers (45 percent), in 1949 among the 45 finalists, the Public League produced 8 scorers (18 percent).

With the absence of Coach William Mackie during the war, DuSable continued to field a team, but without the same rigorous training. The 10-mile marathon program, for instance, was abandoned. In the 1945-46 season, Mackie returned to DuSable. He reinstituted the 10-mile marathon and soon brought the school to even greater prominence in the Chicago swim world. The first two years he lost a few contests, but in the in the 1947-48 season, the school went undefeated in dual meets and won the championship of the Central Section. By this time, the Board of Education had instituted dual-meet leagues to supplement the fall and spring meets. In the fall 1947 meet, Donald Clark became the second DuSable swimmer to ever win an individual title, when he took the Junior breaststroke. The following spring, in the city meet, Eddie Kirk was became the third DuSable individual winner, when he grabbed the 200 freestyle. The Board also introduced a new rule for the annual meets, limiting the number of competitors for each event to two per school. The Lane Tech yearbook opined that the rule "was installed to prevent Lane from completely swamping the other schools."

Meanwhile, in the 1948 state meet, New Trier became the new dynastic swim power in the state meet, beating Lane Tech narrowly 31 to 26 points. Proviso High came in a close third with 25 points, the team spearheaded by future Olympian Jerry Holan in the breaststroke. Lane Tech would have won the meet had not its 150 medley relay team been disqualified. Swimmer Tom Gibe was charged with not making contact with the wall on his turn. The yearbook rendered the verdict as "New Trier beat us out in the state meet when Tom Gibe was disqualified for missing a turn he did not miss." New Trier was now producing top swimmers, notably freestyler Buddy Wallen (son of the great namesake swimmer) and Bob Kivland. This defeat did not end the great teams at Lane Tech. In the program, Coach Newman was training a freshman swimmer by the name Ron Gora, one of the greatest swimmers to come out of Illinois. Gora explained how he entered the program: I went out to football, and I got injured the very first practice. I got hurt on the knee, and the doctor who was giving me the rehabilitation recommended that I take up swimming—just lounge in the pool, hold on the back of the walls, and stroke my legs up and down, like in the backstroke. As I was always on the wall with my arms on the gutter and my head towards the wall, and lifting up my feet to backstroke position to kick, I developed a real strong kick. Coach Newman saw me and noticed I had some potential. He talked to my Dad about me coming out for swimming, and I joined the team as a backstroker.

In one of the city's junior championships, Gora broke one of the great Adolph Kiefer's backstroke records, but he also broke one of the freestyle records. Kiefer who was actually there officiating at the meet, turned to Gora after he broke his record, joked, "Stay on your stomach!" Gora went during his career to break several national high school records, many city records, and a bunch of state records, competing in backstroke, individual medley, and freestyle. "During my career in high school, college, and as an amateur," said Gora, "I had set some 32 swimming records."

In 1949, Lane Tech was still in the hunt for the state title, but it lost to New Trier by a score of 43 to 32. Again Proviso came in third with 26 points. The star swimmers of the meet were sophomore Ron Gora, who won both the 100 and 200 meter freestyle events, and Proviso's Jerry Holan, who won the breaststroke in record time and led Proviso to the medley relay title. Both swimmers would represent the United States in the 1952 Olympic Games. The Chicago Public League by this time was clearly in decline in terms of generating swim talent. Whereas a decade earlier, seven Public League schools were represented in the finals in 1949 only two made it, Lane Tech and Steinmetz. Whereas in 1939 among 40 finalists, the Public League produced 18 scorers (45 percent), in 1949 among the 45 finalists, the Public League produced 8 scorers (18 percent).

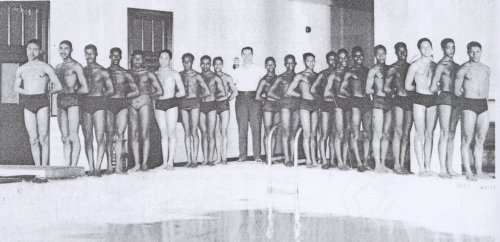

DuSable, Spring 1949

At DuSable, the swimming program under Coach Mackie continued to make gains during the 1948-49 season, repeating as Central Section champs. In the city-wide meets, Lane Tech was still dominant, despite the rule limiting each school to two contestants per event. In the April 1949 long course meet, for example, the north side school took first with 51 points, followed by Crane in second place with 18 points, Taft in third with 15 points, and DuSable tied with Tilden Tech for fourth place with 14 points, getting a second from freestyler Eddie Kirk, a first from diver Leon Guice, and a fourth in a relay.

The racism of the earlier years no longer seemed to be evident. There were no published reports of resistance from those schools as in earlier years. Most of the DuSable swimmers did not see any conflict or sense any animosity. Commented DuSable star Eddie Kirk, “We knew them and they got to know us pretty well. It was just like a group of fellows getting together and swimming. That’s one of the things I feel real comfortable with, because whenever I went during the summer, the Chicago Tribune meet, the Herald American Meet, and a couple of AAU meets, it seemed as though I was welcomed wherever I went.” Said backstroker Jerome Merritt, “When I swam against those teams I was treated right, nobody said anything negative or nasty, or anything at all at those meets.’ Champion breaststroker Donald Clark recalled, “I can honestly say that with regard to the guys were competed against, we never had any racial incidents that I recall. In fact, back then I received a lot of compliments from my competitors. I was spurred on by a lot of fellows on the white teams.”

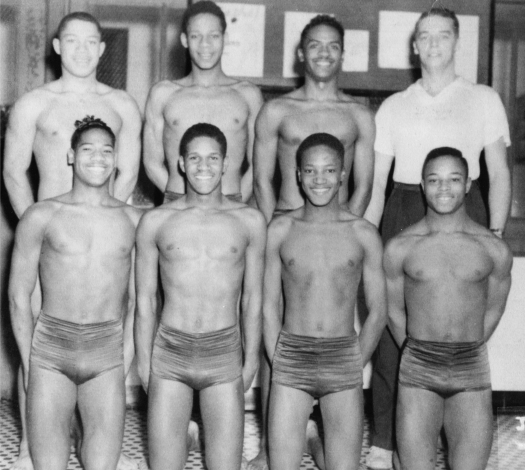

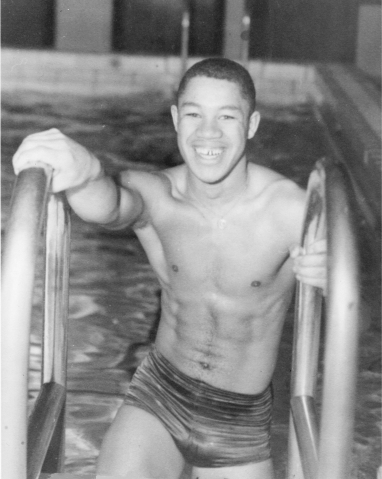

Coach Mackie, Eddie Kirk, and Donald Clark

William Mackie is fondly remembered by the swimmers of this period as an excellent coach. The swimmers gave a number of reasons. Related Kirk, “He had high expectations that he wanted you to meet and he made sure you did the work to achieve those goals.” In addition to the daily afternoon practice sessions, the team met each Tuesday and Thursday morning at 8:00 AM for training. Diver Guice added, “Coach Mackie taught us a lot of things about swimming that we didn’t know coming up, and he was interested in getting us involved in different competitions during the school year.” Added breaststroker Clark; “He would explain things to you. Mackie had shown me how to do a radical new turn with a flip over. This was questioned at a meet, but he got them to accept the maneuver. I thought he was a heck of a coach.”

Mackie is also recalled as something of a stern coach. James Brown, who took one of Mackie’s swim classes, related, "When he said something you had better listen. He was one of those kind. The guys would respect those coaches back in those days, whether they were on the swim team or not." Added Clark, “I don’t know how to put it, but Coach Mackie had a manner. If you want to be on the team you were going to do it his way. But without doubt he was a very likable guy. He was what we used call back then a cool guy.” Backstroker Jerome Merritt commented, “Everybody on the team liked him. He was a very interesting, very fun coach, just an all-around nice guy.”

The success in swimming that DuSable was experiencing in these years was not only due to training regimen imposed by Coach Mackie. The swimmers he had were highly dedicated to swimming and augmented their in-school training outside the school. Team captain Eddie Kirk worked as a lifeguard at the Wabash YMCA and several evenings each week. Said he, “There was seven of us, and I was bringing the fellows in at least two or three times a week, practicing in the pool, and that’s what helped us along a little bit, because we were like doing double practice.” Kirk also served as unofficial assistant coach and worked with the swimmers on their strokes and training. Diver Lloyd Outton who succeeded Kirk as captain proudly recalled taking the team to the YMCA on Christmas vacation and training every day during the break.

Breaststroker Donald Clark did not participate in the group outside practices, but got a lot of training on his own at Washington Park. Two of the lifeguards there were his cousins, Waymon Ward and Wesley Ward, the latter who was DuSable’s top swimmer in 1941, took interest in developing their young cousin. Said Clark, “When I went to go swimming at Washington Park, they made me practice going up and down that daggone pool. That’s how I built up speed.”

Diver Leon Guice first learned to swim in the Washington Park pool, and in his early teens was working as a life guard at the pool and there was introduced to diving. He saw one-time national AAU diving champion and fellow CYO swim team member Dorothy Ziegler training for an AAU competition at the pool. Said Guice, “Dorothy Ziegler was a great influence on me in diving. She would come to the pool and work out and I would watch her. After she finished working out, I would get on the board and try to imitate what she had done. After the competition she would come back on her own and regularly coach me on the various aspects of diving techniques.” Guice passed on what he learned from Ziegler to fellow diver Lloyd Outten. The two would do pairs diving exhibitions at the Washington Park, where in after hours they would practice their dives. The two soon became great point producers for DuSable teams in the next couple of years.

The DuSable swimmers were going beyond most of their competitors at rival schools by putting considerable training outside the school. These extra practices not only helped the team become better swimmers, but undoubtedly helped to bond the team together. “We worked together as a whole and did things together,” related Kirk, “like at the YMCA, and continued to do that for the next two or three years. We never had much money and we would have to walk each other home in the dead of winter after the practice sessions. And as time went on the team got stronger and stronger.” The DuSable Sea Horses were now ready for the great showdown against the powerhouse Lane Tech team in December 1949.

In the 20-yard Public League meet in December 1949, DuSable had its best ever opportunity to overtake the Lane Tech team. The north side school was down that year, and DuSable was loaded. The Chicago Defender, whose sports writer Chuck Davis was following the team, understood that DuSable had a genuine chance of ending Lane Tech's 14-year string of 20-yard titles. DuSable, which did not have the numbers that Lane Tech did, decided not to compete for the junior title and concentrate all its horses on the senior half of the meet. The day before the finals of the meet the Chicago Defender ballyhooed DuSable's chances with a sizable story and a large headline, "DuSable Girds To Upset Lane In Tank Meet." Lane Tech qualified seven individuals and one relay team for the finals, compared to DuSable's five individuals and two relay teams.

Lane, Fall 1949

The two teams were evenly matched for the finals—and clearly DuSable was posed for an incredible upset—but the mainstream papers did not take notice. One should say the unnamed City News Bureau reporter did not take notice, because during this era just about all the small prep stories were written by the City News Bureau and the four dailies merely ran modified versions. The primary narrative of the preliminaries by the News Bureau was the national interscholastic record set by Lane Tech's Ronald Gora in the 220-yard freestyle, and that Lane Tech was favored to continue its string of titles. Neither the Chicago Daily News nor the Chicago Herald-American bothered to mention the number of DuSable qualifiers, giving the readers the idea that Lane Tech had the title wrapped up. The Herald-American even said that Lane Tech was a "heavy favorite." The Chicago Sun-Times and the Chicago Tribune both listed the number of qualifiers of each team, yet the write-ups automatically assumed Lane Tech as the favorite. Nothing was mentioned how DuSable just might have the horses this time to beat Lane Tech. That was not the story.

DuSable, Fall 1949

Lane won the meet, but it was the closest outcome in a couple decades, with Lane Tech edging DuSable by just five points, 46 to 41. The City News Bureau's theme of the story, which was repeated in the mainstream dailies, was that DuSable had been a genuine threat to take the title from Lane. Said the Herald-American, "DuSable put a scare in the Lane seniors." The Chicago Daily News said that the Lane Tech "squad was hard pressed by DuSable to win their title." The Chicago Tribune said that the "seniors were pressed by DuSable to win."

There were no other write-ups by the dailies over this near upset. The Chicago Defender followed the next week with a story lamenting the loss, and the bad breaks in the meet, such as DuSable's defending diving champ, Leon Guice, failing to repeat as champ. The paper also noted that Lane Tech had more than 6,000 male students, compared to DuSable's roughly 1,500 to 2,000 male students.

DuSable's results in the 25-yard meet in the spring of 1950 were not too shabby either, with the school taking second with 33 points to Lane Tech's 45 points. DuSable's star swimmer, Eddie Kirk, that year took home the only medal the school ever won in the state meet, winning the individual medley in the annual March meet. The 1949-50 school year, thus, represented the high watermark of DuSable's achievement in swimming, so to speak.

There was no commentary in the mainstream dailies on the fact that DuSable's all-black team nearly beat the mighty Lane Tech team, and took second in two league meets. The Chicago Defender only briefly touched on it, when Chuck Davis offered some commentary in his column, "Chuck-a-Luck." He said:

One of the sports most neglected by Negro high school boys—and collegians too, for that matter, is swimming. Tennessee State, W. Virginia State, and Howard to mention a few, have facilities for a top flight aquatic program, but for some reason the sport has not clicked.

In the event Negro colleges ever go in for swimming full scale they will find a reservoir of talent in Chicago's DuSable High School. For at least ten years, the school has produced some of the best tank performers in the city...

Davis continued his commentary by attributing the success of the team to the 10-mile marathon that Coach Mackie had been conducting during his tenure. He attributed the lack of swimming success by many black schools to lack of interest and lack of tough training. The success at DuSable was not only due to the 10-mile marathon, one should note, as the school was producing top divers at this time as well as swimmers. Leon Guice was the city's diving championship in the spring 1949 meet and took second in the fall 1949 meet. In the spring and fall meets of 1950, Lloyd Outten copped second place both times.

Despite all the success it enjoyed, DuSable faced much resistance by many of its students to swimming. James Brown, who took a swim class under Mackie. already knew how to swim, which he had learned at the city's park district pools, but he noted that many of his fellow classmates did not, and resisted the swim instruction. Said he:

Coach Mackie would make them get into the water, but they really didn't want to. You could tell the ones who didn't want to swim. They stayed in the shallow water all the time. The one's who didn't want to swim had to go to ROTC!

Brown laughed on the ROTC comment. Students at Chicago high schools at the time could participate in ROTC in lieu of their physical education classes.

DuSable's success in the city's high school swimming program should not be attributed solely to the 10-mile marathon. The school was producing top divers at this time as well. Leon Guice was the city's diving championship in the spring 1949 meet and took second in the fall 1949 meet. In the spring and fall meets of 1950, Lloyd Outten copped second place both times.

Lane Tech and DuSable on their Downward Arcs

In the 1950 state meet, Lane Tech scored only 19 points, taking third in the meet, behind New Trier and the rising power Evanston, who was building a strong program under Coach Dobbie Burton. Ron Gora's two firsts, in the 50 and 100 freestyle, gave Lane 12 of its points. Lane Tech in the 1951 state meet again relied solely on the talents of Ron Gora, who easily won the 50 and 100 freestyle events, getting Lane Tech 12 of its 21 points. The school had dropped down to fifth place, after New Trier (which took its fourth consecutive title), Rockford East, Evanston, and Rockford West. Lane's program like that of DuSable was clearly in decline. Gora at this point in his career was a leading high school swimmer in the nation, competing against the best in the nation in national AAU competition. The day after the state meet Gora took a plane to compete in the Pan-American Games. He would compete in the 1952 Olympics. Lane Tech had a 200-yard freestyler, Gaither Rosser, who took third in 1950 and second in 1951, but who would also make the 1952 Olympic Team, selected for the 800-meter relay team.

With 1950-51 season, DuSable again had a successful season, but it did not reach the heights of the previous season. The school took the Central Section for the fourth consecutive year, and managed to take second in the annual 20-yard meet, but its 14 points hardly challenged Lane Tech's 42 points. A bit more glory was rendered to DuSable with the publication of the amateur swimming guide in early 1951. A DuSable swimmer, Eddie Kirk, was named to the 1950 All-American interscholastic team, and Bill Mackie was given an award for more than 20 years of service to swimming. At that time, the Chicago Defender noted that the school's dual meet record was 108 victories to only 11 defeats. The spring 25-yard meet saw DuSable drop behind Lane Tech, Harrison, and Roosevelt. The program was in decline.

Eddie Kirk, DuSable All-American, 1950

The 1951-52 season marks that last time that DuSable garnered any kind of league-wide achievement in swimming, when it took second to Lane Tech in the annual 20-yard meet, earning 17 points to Lane Tech's 34 points. The largest chunk of points was earned by DuSable's diver, Leon Wade, who took first place. By the spring of 1952, DuSable was no longer contending, getting only six points in the league meet, five of them from Wade's second-place diving finish.

In 1954, the school basketball team, the Panthers, took second in the state under Coach Jim Brown. Mackie, by the way, was the assistant coach on the team. This began a tradition where not only outsiders saw DuSable as purely a basketball power, but so did the school. Said Floyd “Billy” Ray, “The swimmers were no longer coming out for the team. After DuSable’s basketball team went downstate to play in the championship game in 1954 none of the students wanted to swim, they wanted to play basketball.” Donald Clark sadly noted, “I hate to say it, but Coach Mackie just did not have the guys any longer who were willing to put in the work, and maybe the coach was tired at staying on their rear ends.”

DuSable continued with a swimming team, but after the 1956 season Mackie gave up coaching the swim team to move up as chairman of the boy's physical education department. Under subsequent coaches, the team continued to field teams in the next decade, and even captured a couple of Central Division titles, but the glory years were clearly gone.

Mackie left DuSable after the 1965 season, and unfortunately by this time the school was not managing to field a team every year. The yearbooks kept heralding the return of the Sea Horses. The last team fielded by DuSable was the 1972 Sea Horses. Mackie had moved up to become athletic director of the Chicago Board of Education. He retired in 1970, and died in Denver, Colorado, in February of 1981.

Meanwhile, Lane Tech had ceased to be a factor in state competition with the 1952 meet. New Trier had won its fifth straight title with 42 points, followed by Evanston with 30 points, and Highland Park and Maine tied for third with 13 points each. Where was Lane Tech in the standings? Way down in ninth place with only five points. The school continued to win each of the Public League annual meets in fall and spring, but its continued success spoke more of the general decline in swimming in the city schools relative to that of the suburban schools. Before the state meet, the New Trier coach, Edgar B. Jackson, announced he would retire at the end of the school year. Overall the Public League's slide in the state meet paralleled that of Lane. The 1949 figures were even more dismal in 1952. The Public League increased the number of schools from two to three—Lane Tech, Harrison, and Sullivan—but the number of city finalists continued to decline, going from eight to five.

In the 1952-53 school year, Fenger High, under Coach Bill Kresge, began to threaten Lane Tech's dominance in the Public League. Kresge arrived at Fenger in the 1950-51 season, and began building a program. His first year 20 candidates tried out for the team and by 1952 he had 75 students trying out. In the short course meet in December, Fenger took the junior title, ending Lane Tech's streak of wins that began in the fall of 1935. In the long course meet in the spring, however, Lane Tech retained its dominance, besting Fenger 64 to 33. Lane Tech continued to prevail over Fenger in both the junior and senior meets, but the meets were becoming more competitive. In the spring of 1954, in the junior division, Lane barely edged Fenger 48 to 45. The senior division saw Lane prevail over Fenger 73 to 49.

In the fall meet of 1954, when Fenger finally prevailed over Lane 61 to 31, Lane Tech lost its first senior division title in the short course meet since the fall of 1936. The team was directed by Casimir Tabisz, who took over the team when Bill Kresge was stricken with polio. Kresge died one week before the meet, unable to see the triumph of his endeavors. The spring of 1955, saw Lane once again on top, but the following spring, Fenger once again beat Lane in the senior division. In the 1956-57 school year, Fenger prevailed in both the fall and spring meets.

John Newman was having his difficulties as well. In 1956 he suffered a heart attack, and had to forgo coaching in 1957 and 1958. He came back for two more seasons—1959 and 1960—and was able to bring Lane Tech back to championship form, at least on the Public League level. He was not able to return the school back to its glory years of the 1930s and 1940s, when Lane Tech had the best team in Illinois, and sometimes in the nation. As an indication of how far the Public League had fallen in swimming, in the last two years of Newman's coaching career, of the 132 finalists in the two state meets, there was not one Lane Tech swimmer or any other Public League representative. Newman retired at the end of the 1959-60 school year, and died in August of 1963 after a long illness.

Factors in the Decline of the Chicago Schools Swim Programs

Former swimmers at Lane Tech cited a number of reasons why the Newman's program went into decline during the 1950s. Ron Gora looked at the 1948 state meet as a critical turning point. That meet saw the Lane Tech medley relay team get disqualified because a judge charged that Tom Gibe failed to touch the wall on his turn. The disqualification of the team was enough points to keep Lane from winning the state title. With that meet, New Trier began its swim dynasty. Said Gora, "Tom Gibe swore to his dying day that he touched the wall. That was really a discouraging thing that happened, and with the graduation of all those guys in the next year or so, the Lane Tech team just dwindled down to nothing and there was not much interest."

But in previous years, Lane Tech, as they say in the sports arena, had so much talent it always reloaded. The former swimmers agree that the failing health of "The Judge" was another crucial factor. McKinley Olson explained, "John Newman was a very very heavy cigarette smoker. He was smoking all the time, constantly smoking, and his hands and fingers were stained with cigarette smoke. So I think probably his health declined." Harold Gold added, "You go into his office, he was always smoking a cigarette, but he never did around the pool." Jack Masters related, "What happened was he had heart problems. He got ill, just couldn't handle it anymore. Other people were taking over for him, and they didn't know the stuff he knew. He was well ahead of his time."

But there were institutional changes in swimming that adversely impacted on the Lane swimming programs and those of other Chicago public schools, as the former swimmers make clear. One was the development of age-group swimming. Explained Olson:

There were a number of things that happened. For one, all the suburbs developed what they called age-group swimming programs. Usually the coach of the age-group swimmers was the coach of the high school in the neighborhood as well. By the time these kids get into high school you don't have to teach them the strokes, you don't have to teach them the drills. They are already accomplished swimmers. Some of the great Lane Tech swimmers of the past, like Otto Jaretz and Henry Kozlowski, didn't really swim before they got to Lane.

And on top of that the suburban high schools are set up that they are more or less like community schools. In other words, their facilities, like swimming pools and gyms, are open on weekends, whereas the Chicago Public Schools with the union rules, they're never open.

Touching on the decline of swimming in the Public League in general, Master pointed out that in the 1950s "there was a resurgence of the suburban schools, and that the suburban schools HIRED their coaches. In the city public schools, you were assigned to a school and if they needed a swim coach, you were the swim coach. It didn't matter what you did on the outside." Ron Gora cited as an example the fast growing Evanston High program, saying, "Evanston started a program that was fantastic. They would have these real long workouts that developed some exceptional swimmers."

Training techniques in competitive swimming in the high schools also were becoming much more intensive, which perhaps some of the veteran coaches, such as Newman, were not keeping up with. Said Olson:

When we swam in high school our daily workout would consist of kick 500 yards, then we pulled 500 yards, and then we swam 500 yards. Then we might sprint ten lengths, that's 250 yards. Thus most high schoolers at Lane swam 2,000 yards a day. Now in these age-group programs, these kids—ten, eleven, twelve years old—probably swim 5,000 yards a day. Another drastic change was that swimming adopted from track what they call interval training. Instead of swimming 200 yards straight through, you would swim 50 yards, then you would repeat another 50 yards, repeat another 50, and repeat another 50.

There was another thing that was different then. It was considered that any kind of weight training was verboten, because the idea was that if you were a swimmer you needed supple muscles. The theory was that if you lifted weights you would get knotty hard muscles. So it was discouraged. Now every kid does weight training. Newman got older, and the whole concept of swimming just changed drastically.

John Newman's legacy was one of the great programs in Illinois high school swimming that produced the Lane Tech dynasty of the late 1930s and 1940s and brought the Chicago Public League in the forefront of high school swimming in Illinois.

Acknowledgements: The author thanks the following interview subjects for their time and cooperation in sharing their swimming memories: James Brown, Donald Clark, Harold Gold, Ronald Gora, Leon Guice, Edward Kirk, Esther Kirk, Ginny Malter, Jerome Merritt, Jack Masters, McKinley Olson, Floyd “Billy” Ray, and Dick Zachary.

Footnotes available upon request. Published with permission. All rights are reserved by the author.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Illinois High School Association.