The Glorious History of High School Speedskating In Illinois

1921 to 1988

By ROBERT PRUTER

Speedskating in Illinois was a high school sport from the early 1920s to the end of the 1980s, and for most all of its history it thrived solely in the Chicago public high schools. The Illinois High School Association has never sponsored a speedskating competition, but what is generally unknown is that the IHSA (when the organization was called the Illinois High School Athletic Association) sanctioned an outdoor speedskating state meet for two years, 1938 and 1939.

This history of speedskating in Illinois high schools constitutes many stories. More broadly it is the story of the sport in the state, and in more discrete parts, the story of the Olympic speedskaters produced in the high schools, the story of intercity rivalry, the story of the Chicago Public League competition, the story of fantastic community and newspaper support for the sport, the story of the IHSA sanctioned state event, and finally it is the story perseverance and dedication of a few Chicago coaches attempting valiantly to save a dying sport.

In contrast to the East—where speedskating became a high school sport in the 1890s--Chicago high schools were far behind, not adopting speedskating until the 1920s. However, the sport had been flourishing in the city for more than two decades with formal competition among men and women, boys and girls, organized in teams sponsored by private clubs, playgrounds, and parks. The youth of the city was active in speedskating to a degree unknown in any other major city in the United States.

The Intercity Schoolboy Contests

The progress of Chicago in speedskating was spectacularly manifested in 1921 and 1922 in a series of schoolboy competitions among the major cities of the northeast. They involved considerable hoopla with inch-high newspaper headlines, parades, coaching by national champion skaters, and festive parties. These contests were initiated and promoted by Chicago Mayor Big Bill Thompson whose governing approach was to give Chicagoans bread and circuses as he allowed corruption and sleaze to spread through city hall. The impetus came from a challenge made by Thompson to the Mayor John F. Hylan of New York. It was accepted and the Chicago schoolboys would meet the New York schoolboys in the Brooklyn Ice Palace in the first week of March 1921. The mayor formed an ice skating committee, which included such notables as J. Ogden Armour, William Wrigley Jr., and Marshall Field, who provided the financing for the trip.

George Thomson (Schurz), Leon Emmert (Senn), and Howard Storch (Senn)

of the 1921 schoolboy team. Chicago Tribune, 6 February 1921

Tryouts were held to whittle down 176 candidates to a team of 18. The 18 racers were divided into three teams of six grammar school, junior high (first two years), and senior high (last two years). All the schoolboys were identified by the school they attended, which included three racers from Senn, two each from Lane Tech and Austin, and one each from St. Ignatius, Harrison, Englewood, Schurz, and McKinley. This group included two future Olympians and Hall of Fame skaters, O'Neil Farrell (Austin) and Eddie Murphy (St. Ignatius), and Cornelius Ewert (McKinley), a future Silver Skates champion. The enterprise rapidly grew in scope, so that the Chicago schoolboys' itinerary grew to include competitions along the way in Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia before the big race in New York.

On February 26, a Chicago schoolboy team of 18 grade school and high school competitors began their tour. The Chicago papers noted that the Chicago team was handicapped, because all the competition was in indoor rinks, on which the Chicago schoolboys had little experience. Nonetheless, in every city they stopped, they beat the competition by one-sided scores. In Cleveland, the Chicago skaters were so overwhelming that they took all the places, not a Cleveland skater "showed." In Pittsburgh, the Chicago skaters outscored the home team 55 to 22, taking four out of the six races. The Philadelphia contest was so uncompetitive that the Chicago skaters conceded handicaps in each race, from 30 to 70 yards on each event, and still won easily.

In New York, the competition was expected to be considerably better, but it was only minimally so. The Chicago schoolboys took eight out nine events in front of the mayors Hylan and Thompson sitting in the balcony box. Chicago could have easily swept all the events, had not the Chicago's lead skater on the final turn fell taking out another Chicago skater in second place.

In 1922, Chicago chose to serve as host for a national meet; four cities responded to invitations—Milwaukee, Detroit, Cleveland, and New York. Again the competition was divided into three divisions—grammar school, junior high, and senior high. In tryouts in late January among 144 boys, 18 boys were selected, among them previous year competitors O'Neil Farrell and Cornelius Ewert. National champion Roy McWhirter was hired to coach the team, and the Tribune reported, "all of the skaters have been training for several weeks under the coaching of experts." Unlike the previous year, when all the competition was held in indoor skating rinks, the competition in Chicago would be held in the Chicago manner, outdoors on the lagoon at Garfield Park. As the meet was being held in late February, a backup plan was made for the meet to be transferred to a big ice arena in Milwaukee if the weather was too warm, indicating Chicago did not have a suitable indoor facility. As expected Chicago dominated the contest on February 25, winning first place with 40 points, followed by Cleveland with 30 points and Milwaukee with 19 points. Detroit and New York trailed far behind with 4 and 2 points respectively.

Reasons For Chicago's Schoolboy Dominance

An area's success in any sport may be due to geographic factors, demographic factors, or cultural factors, and the success the Chicago schoolboy competitors enjoyed against other cities was due to all three in this case. In terms of geographic, Chicago's sufficiently inclement climate provided more outdoor ice surfaces than other most other cities of the northeast. The demographic relates to not only a large population base but also to the largest Norwegian population base outside of Minneapolis-St. Paul, a group that significantly originated and developed the sport in America. Cultural relates to the many private and public institutions of Chicago that helped immeasurably to spread the sport beyond the Norwegian base.

While speedskating existed to varying degrees in most cold climate areas of United States, the sport was largely and narrowly centered in three cold-weather areas—upstate New York, Minnesota, and Chicago. It may seem self-evident that cold climate cities produce speedskaters, but this element demands an examination with more nuance, namely that climatological conditions can be only properly appreciated as a factor when combined with other factors, such as demographic and cultural. Based on this understanding, Chicago had a decided advantage over most large cities in the early 1920s. Taking an average of the January temperature, the key month for speedskating, only Milwaukee (21.8 degrees) and Minneapolis-St. Paul (10.8 degrees), had colder climates than Chicago (27 degrees). Other cities were higher, namely Cleveland (29.7 degrees), Pittsburgh (30.4 degrees), Philadelphia (35 degrees), and New York (34.5 degrees).

With regard to demographics, in 1920 Chicago produced more young boys aged 10 to 19 (210,000) than any other city next to New York (470,000), meaning more youthful athletes and more skaters. For comparison, Minneapolis-St. Paul had 45,000 boys in this age group; Cleveland, 63,000; Pittsburgh, 50,000, and Philadelphia, 147,000. Naturally, one would expect that these greater numbers would yield more champion skaters. New York, which includes all the boroughs—Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Bronx in particular—naturally had the greatest population of all the cities examined. Yet the New York advantage in youthful population, however, is offset by disadvantages in climate. When you look at New York there were not the abundance of outdoor rinks in the parks and playgrounds, in part because there was not the number of freezing days to make them useful facilities. On the other hand, where Chicago had virtually no indoor skating rinks, New York had a plethora of indoor skating rinks.

Having a sizable Norwegian population proved critical in the early decades of the last century to producing top-notch skaters. Only three United States cities had more than a negligible number of Norwegians--New York, Chicago, and Minneapolis-St. Paul (treating the latter as one metropolis). The results of the 1900 census yielded something of a mild surprise, where Chicago's Norwegian population of native born and parentage residents (38,000) is followed by that of Minneapolis-St. Paul (26,000) and New York (16,000). In 1920, Chicago dropped to second, as the Norwegian population totals were New York (40,000), Chicago (45,000), and Minneapolis-St. Paul (52,000).

Olympian and Hall of Fame skater Eddie Schroeder, who competed in the 1920s and 1930s, pointedly asserted: "The origin of competitive speedskating in Chicago came from the Norwegians, who lived around the Humboldt Park area--that's where it all started." Norwegian emigration to the United States began in 1825, and by 1910 nearly 700,000 Norwegians had come to America. Originally the Norwegians settled in the East and in rural areas. By 1900, however, some 80 percent of the Norwegian-American population had settled in the six Midwest states of Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin, Minnesota, South Dakota, and North Dakota. After 1880 the Norwegians increasingly settled in big cities, primarily Brooklyn, Chicago, and Minneapolis.

Chicago received its first Norwegian immigrants in 1836. The Norwegians settled in two areas in the northwest area of Chicago--the Humboldt Park area and the Logan Square Community--where by 1900 the bulk of the 38,000 Norwegian immigrant population settled. Like most immigrants, the Norwegians attempted to retain their language and culture, and founded churches, schools, and innumerable clubs to help retain their heritage. The clubs included various lodges, singing groups, welfare groups, and such athletic groups as the Norwegian Turners' Society and Sleipner Athletic Club.

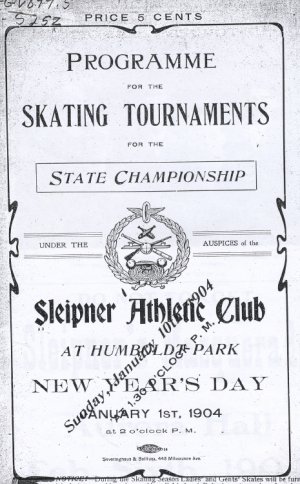

Norwegians formed the pioneering speedskating clubs in Chicago, and their neighborhood park, Humboldt Park, became their playground and the center of speedskating activity. The Sleipner Athletic Club was organized in 1894 as all-around athletic club, but it became especially famed as the originator and chief sponsor of speedskating races in Chicago. Its first speedskating meet was held in 1896, and from 1901 to 1905 Sleipner billed its meet as the Illinois State championship. Another early Norwegian immigrant club and sponsor of major competition was the Northwest Skating Club, formed in 1904. These were not small meets, and they appeared to attract far more than Norwegian onlookers judging by the number of spectators. At least 30,000 fans witnessed both the 1903 and the 1904 Sleipner meets. The Northwest Skating Club meet in 1905 pulled in some 25,000 fans.

Program for the Sleipner annual meet, 1904

A substantial part of the country's skating industry developed in Chicago. The Norwegian settlement around Humboldt Park produced three of the leading skate manufacturers in the United States, all founded by Norwegians. They were Nestor Johnson, Alfred Johnson, and F.W. Planert & Sons. The Nestor Johnson Company, according to one source, invented the modern racing skate. Skaters in the nineteenth century had attached wooden slabs with runners onto their shoes. Nestor Johnson, who owned a bicycle shop, took the concept of steel tubing from bicycles and used that to build a tubular frame to hold the skate blade and to attach it permanently to the shoe.

Nestor Johnson advertisement, 1904

By 1905, a whole array of skating clubs had been formed in Chicago, usually based in the city parks, such as the Douglas Park Skating Club and the South Park Skating Club. The sport was rapidly becoming a citywide phenomenon, while the Norwegian-Americans continued to dominate the high-end competition. As early as 1909, some school playgrounds were conducting speedskating meets in Chicago; and in 1913, the municipal authorities conducted a citywide playgrounds skating meet. By 1921, the annual playground meet was attracting 10,000 participants.

In 1917, the Chicago Tribune, under the encouragement of its sports writer Walter Eckersall, began sponsorship of the Silver Skates competition. The annual event began with just a Senior Men competition, which was naturally won by a Norwegian-American, Art Staff--and quickly expanded, adding a Junior Boys event in 1919, and three other age-group boys' events by 1931. A Senior Women's event was added in 1921, a Junior Girls event in 1922, and later other girls' events. In the early years, Norwegian-Americans won most all of the competitions, but by the mid-1920s one begins to see names of other ethnic groups among the Silver Skate winners.

The Silver Skates proved to be a watershed event, as the Chicago Tribune not only almost daily promoted the Silver Skates competition but also reported on every other meet, high and low, in the city, thus generating a huge interest and growth in speedskating. The Tribune competition helped to bring thousands upon thousands of Chicagoans and suburbanites, boys and girls, women and men, to skating competition as they flocked to the outdoor skating rinks and skating ponds and lagoons preparing for the annual Silver Skates. By 1923, the Chicago area in the wintertime was dotted with more than 600 outdoor rinks (more than any other city), and thousands of boys and girls of all national origins were skating. Out of its Norwegian origins, speedskating had become an all-American sport. The Norwegians had participated in speed skating as part of their ethnic heritage, and by doing so gave all of Chicago a sport in which the city excelled.

Thus by the 1920s, Chicago supported an array of the public and private institutions of the city—skating clubs, schools, newspapers, and the municipal governments all acting together produced a powerful cultural milieu that encouraged and promoted speedskating in Chicago for all residents. The Chicago advantage was clearly evident authorities in the cities that were defeated by Chicago in the 1921-22 meets, and attributed it to the tremendous institutional support for the sport; both private and governmental. In the report from Cleveland on the 1921 meet, the Chicago Tribune noted, "The Chicago lads displayed what the Cleveland youths lacked, the result of a municipal organization to foster the sport among school children." Mayor Big Bill Thompson, who attended the New York meet with his New York City counterpart, was reported by the New York Times to have, "magnanimously deplored the lack of training facilities for the local lads as compared to the abundant outdoor rinks available in Chicago."

The speedskating infrastructure did not let up during the 1920s. The Silver Skates grew tremendously, becoming the preeminent skating event in the country, attracting up to 60,000 fans and thousands of participants during its heyday in the 1920s and 1930s. The city's playgrounds also broadened its meet to include a girls' competition, and the city's park district began a separate speedskating competition. These competitions continued for decades afterwards through to the 1970s and helped to supply competitors in the Chicago public high schools.

The Public High School Tournament

The intercity competition of 1921-22 energized Chicago school authorities to belatedly add a high school tournament in 1923, thus finally bringing high school competition into the rich array of skating competition already available for the city's youth. The first meet was held in mid-January, and provided competition in two divisions, junior (age 16 and under) and senior. Each division included two individual events, 440 yards and 880 yards, and a mile relay. The meet drew 16 schools and 173 racers. Englewood High won the senior division, and Austin won the junior. Englewood's Eddie Brignall, who represented Chicago in the intercity matches of 1921 and 1922, was the star of the meet. Another veteran of the intercity matches competing in the league meet was Cornelius Ewert of McKinley.

Laudable as it was to add speedskating to the Chicago Public High School League program, no plans were made to include a competition for girls. The high school girls in the city were highly active in club, playground, and Silver Skates competition, and in some high schools had formed girls teams, but school authorities were blind to that possibility. High school girls of the 1920s who became future Hall of Fame skaters were Elaine Bogda (from Schurz), Helen Bina (from Lake View), and Elizabeth Dubois (high school unknown).

In 1924, the league added an individual one-mile race to the meet program, and participation rose to 192, 101 in the junior competition and 91 in the senior. Austin captured the first of its five senior titles and of its six junior titles it won from 1924 to 1935. The 1926 meet—which was won by Schurz in the senior division and Austin and Schurz in a tie for the junior division—saw the first participation of skating whiz Eddie Schroeder of Tilden Tech. He won the 880-yard in the junior division. In 1928 he helped lead Tilden to its first of three consecutive senior titles, taking two seconds, in the 880-yard and one mile. In 1932, he would participate in the 1932 Olympic alongside fellow ex-schoolboy aces, O'Neil Farrell (Austin) and Eddie Murphy (St. Ignatius) who had represented Chicago in the intercity contests of 1921 and 1922.

Schurz 1926 skating teams, the junior Public League co-champs and the senior Public League champs.

The Chicago Public League revived the intercity schoolboy competition in 1929, when it sent a representative team to Lake Placid, New York, to compete for the annual Adirondack Gold Cup championship. Among the members of the team was Eddie Schroeder of Tilden and future Silver Skates champion Eddie Stundl of Harrison Tech. The team consisted of 16 racers divided into juvenile (under 14 years), junior (under 16), and intermediate (under 18). The Chicago schoolboys easily took the team championship, with a total number of points that exceeded all the other cities combined. However, the competition was largely limited to local racers from Lake Placid and Lake Saranac. These upper state communities did indeed constitute one of the hotspots of schoolboy skating in the country, but represented a small population base as compared to that of Chicago.

Because of an early 1930s warm spell, several of the Public League skating meets were held indoors—in the Chicago Stadium in 1932 and 1933, and in the Coliseum in 1934. The 1932 Public League meet, which Austin was for the second year in a row, featured another future Olympian and Hall of Famer, Leo Freisinger of Schurz High. The senior knocked an unheard 30 seconds off the record for the mile distance, and in 1936 represented the United States in the Olympic Games.

Austin High skating team, 1930

The State Meet

The late 1930s saw the domination of the Tilden Tech team. The school took five consecutive Public League titles from 1935 through 1939. The Tilden skating team, first under coach Earl Solem and then under Louis P. Christoffel, was supported by one of the largest skating clubs in the city. The Tilden Skating Club in the late 1930s regularly supplied more skaters to the Silver Skates competition than any other club, supplying 70 racers in the 1939 meet. The Public School meet that year was prospering as well as it was in the 1920s, attracting 180 speedskaters from 12 schools for the junior and senior competitions.

On January 29, 1938, the Illinois High School Athletic Association (IHSAA) sanctioned the first invitational state high school skating meet in Aurora. The meet was hosted by the Aurora Playground and Recreation Association on Mastodon Lake. The event attracted 79 skaters, and brought Chicago schools in competition with schools outside the city for the first time. Eight schools participated, two from Chicago (Tilden Tech and Crane Tech), four from the Fox Valley (Elgin, West Aurora, East Aurora, and Geneva), and two downstate (Rockford and Urbana).

As the meet was sanctioned by the IHSAA, all entries had to be submitted through the office of its director, Charles V. Whitten, for eligibility. Only IHSAA member schools could participate, which may have explained the low turnout of Chicago schools. At that time the Chicago schools joined the IHSAA individually, and most chose not to be members. The IHSAA also limited participation to schools within 75 miles of Aurora, obviously fearful of an outside meet growing into a national event, as did many meets during the 1920s. The teams of the schools outside Chicago appear to be ad hoc teams, formed for the sole purpose of participating in the state meet. A check of the yearbooks of Elgin, West Aurora, and East Aurora finds no mentions of skating clubs (except for girls) and no mention of the state meet participation. The local Elgin paper noted that this was the first year that the school ever had an ice skating team for competition against other schools.

Tilden Tech dominated the meet with 275 points, followed by Elgin with 110 points, East Aurora with 75 points, and Crane Tech with 10 points. No other schools scored points. Elgin High, which was centered in one of the hotbeds of skating in Illinois, might have done better if its top skater, Lowell Miller, had not chosen instead to skate in the North American championship being held the same day in St. Paul, Minnesota. At the event he won the intermediate championship.

Elgin at this time was well aware of its growing reputation as a speedskating center. The Elgin Ice Skating Club annually sponsored the Tri-State Meet, which attracted up to 400 of the top speedskaters from around the Midwest, and many of the winners came from Elgin. Boasted the Elgin Daily Courier-News, "Elgin is definitely on the nation's ice skating map, not only as the scene of one of the country's outstanding meets, but also as producer of talented speed artists."

In the Chicago Tribune story on the meet, it was reported that the coaches of the teams voted to make the meet an annual affair and to ask Whitten to sanction an indoor state meet in March at the University of Illinois. Apparently, nothing came of the indoor meet, but the coaches were able to conduct a second state invitational in late January the following year, which attracted 102 skaters. Eight schools participated—five from Chicago (Tilden Tech, Crane Tech, Austin, Farragut, and Hirsh) but only three outside the city (Elgin, East Aurora, and Plainfield).

Tilden again swept the competition with 370 points, followed by Crane Tech with 50 points, Elgin High with 30 points, Austin with 20, and East Aurora with 10. The three other schools failed to score. Tilden won all five of the individual events and the two relays. The event attracted 500 onlookers.

The officials for the meets included faculty members of the two Aurora high schools, Illinois Skating Association officers, and IHSAA officials. The exceptional nature of the IHSAA sanctioned raised a comment by the Aurora Beacon-News: "A meet of this nature is very seldom sanctioned by the state association when sponsored by any agency other than a high school, and Aurora can be proud that the city playground and recreation department has fulfilled the requirements specified by the association and received the sanction."

The Aurora Playground and Recreation Association chose to discontinue the meet after two years. The participation of schools outside of Chicago and the Aurora schools was down in the second year (from nine to six for East, and from two to zero for West) and the overwhelming domination by Tilden Tech probably dampened the enthusiasm for continuing the annual event.

Chicago Public School Olympians

The Chicago Public School speedskating program continued to prosper in the 1940s, and served as an incubator of Olympians for the United States. Dick Solem of Austin and Ken Henry of Taft were two members of the 1948 Olympic skating team who originally appeared together in the 1944 Public School meet. Solem established a new Public League record in the 440-yard dash in the senior division, and Ken Henry won the 880-yard race in the junior division. For the next three years, 1945-47, Henry competing in the 880-yard and mile races led Taft High to three consecutive Public League titles. The 1948 meet, which saw Lane Tech break Taft's dominance, saw the participation of 1952 and 1956 Olympian Chuck Burke, from Foreman High.

The Olympic skating competition was dominated by European competitors, partly because they regularly competed in their home countries in the Olympic-style racing, against the clock while paired with one other racer. In the United States, the skaters still competed in mass start, or pack-style, racing, in which skaters raced against each other from a common starting line. This put American skaters at a disadvantage in international competition. Ken Henry won the gold medal in the 500 meters in 1952 Olympics, and this was a huge breakthrough for United States skating. However, in the 1956 Olympics, Henry could not repeat his success, falling down to 17th place in the 500.

The Chicago Public League competition remained robust throughout the 1950s, attracting 150 skaters in the 1954 meet. Eleven schools participated in the senior division, which was surprisingly won by Kelvyn Park, which in most years in the history of the meet did not even field a team. But decline within a few years would set in.

By the early 1960s, most of the skating talent was being developed in the suburbs, particularly in Northbrook and Glen Ellyn. In Chicago—which for years had nurtured skaters in the playground programs, particularly through the Pierce Playground—the sport was in decline and each year fewer and fewer good skaters could be found in the schools.

From 1958 through 1964, the Lindblom High skating team, coached by George A. Von Bremer, who was also the school's football coach, took all the Public League senior team titles. The top skater to emerge in the Public League competition in the 1960s was Mike Passarella of Steinmetz, who made his debut in 1962, when he took the junior 880-yard title. In 1963 and 1964, he won the one-mile competition in the senior division. Passarella noted that at Steinmetz he was competing essentially without a coach, as the faculty member who officially served as the coach knew nothing about speedskating. Passarella skated for the venerable Northwest Club, which was founded in 1904 by Norwegians. In 1968, Passarella represented the United States in the Winter Olympics.

Demise of Public League Speedskating

From 1967 through 1973, and annual Public League meet was dominated by the Senn and Lane high schools—Senn winning five titles (one shared with Lane), and Lane three titles. By the early 1970s, the Public League skating meet was in severe decline, as was pack-style racing in Illinois in general. With the retirement of George A. Von Bremer from Lindblom in 1971, less than a handful of coaches continued the program. In the 1973 meet, only three schools—Lane Tech, Senn, and Chicago Vocational—fielded full teams. The meet was completed in less than two hours, whereas in earlier decades more than a dozen schools competed in each division in a meet that lasted all day into the early evening. The Senn coach, Sal Loverde, lamented to the Chicago Sun-Times reporter, "All the interest now seems to be in hockey. I put out a call for my speedskating team and only 15 turned out. And we're from an area where there are many rinks available."

The decline of speedskating in the Public League reflected the broader decline in the sport during the early 1970s from a combination of climatic and institutional factors. Said Jack Morell, coach of the 1992 United States short course team, "In the early 1970s there was a warm spell where there were a lot of cancelled meets. That helped considerably to kill the outdoor sport. By the end of the decade skating meets were being held indoors." And then after the 1974 Silver Skates meet the Chicago Tribune ended its sponsorship, and explained Morell, "That had a lot to do with the decline. The coverage of Silver Skates was ended, and the paper no longer covered the other skating meets either."

The Chicago Tribune last mentioned the public league meet in its "Scoreboard" section in 1971. Thereafter, only the Chicago Sun-Times reported on the meet, usually writing a sizable story each year, and the theme was always on the meet's decline. A 1975 story said that the Public League meet was being continued through the efforts of four coaches—George Dayiantis of Lane Tech, Rudy Rinka of Amundsen, Sal Loverde of Senn, and Chuck Binder of Schurz. The paper noted that the four coaches shared duties as starters, judges, and timers, but for only a mere dozen skaters. The coaches in the off season would use their own money to buy skates and then try to find athletes who could pretend to be speedskaters for at least one day each year.

The 1976 meet, won by Lane Tech, saw the introduction of female competitors. Pat Halloran of Amundsen finished third in both the 440 and 880, providing Amundsen's only varsity points. Other women competitors were Karen Reykalin and Suemee Lee of Amundsen and Marilyn Javor of Schurz. The theme of the Sun-Times report was typically on the sport's decline, but with a twist that just maybe the girls would help rejuvenate the annual event.

That did not happen. There was not much competition in the meet throughout the remainder of its history. From 1974 through 1980, Lane Tech took every junior and senior championship. In the 1978 meet there was a brief uptick, when the teams from Lane Tech, Amundsen, Senn, and Schurz were joined by two more schools, Taft and Young. The quality of skating left much to be desired, Bill Drozd of Schurz, an all-state soccer player who took fourth in the mile, cracked to the Sun-Times reporter, "I think I might have gone faster against that wind without skates."

The years 1981 and 1982 saw Taft under Coach John Swider win the Public League title, ending Lane Tech's long dominance. The Taft 1981 team included two female skaters, Beth Hickey and Linda Culliton, and the following year Culliton won the 880-yard race, the first title by a girl in the meet. Swider was the father of Nancy Swider, who participated in four Olympic Games from 1976 through 1988, but she attended Taft prior to Taft's participation in the Public League meet. In 1984, the coaches could only rustle up fourteen skaters to compete, and two varsity and 12 frosh-soph medals went unclaimed. Lane Tech, which won the varsity division, also won the frosh-soph division as the only full team competing. In 1988, the Public League conducted the last reported meet, and probably the last meet. Lane Tech won both varsity and frosh-soph division over two other schools, Taft and Amundsen.

The demise of high school speedskating in Illinois ironically took place during an era when Illinois was one of the leaders in producing national and Olympian speedskaters. From Northbrook came Eddie Rudolph, Betty Buhr, Neil Blatchford, Sally Blatchford, Anne Henning, Leah Paulos, Lydia Stephans, Andy Gabel, David Cruikshank, and Debra Cohen. From Glen Ellyn came Becky Sundstrom, Shana Sundstrom, and Cindy Darrow. From Des Plaines and Park Ridge came Barbara Lockhart, Gary Jonland, Paul Jacobs, Debbie Carlstrom, Frank Filardi, Mark Greenwald, and Pat Moore. From Wilmette and Winnetka came Diane Holum, Jan Goldman, Hilary Mills, and Nathaniel Mills. From Evanston and Skokie came Celeste Chlapaty, Jack Mortell, and Jeff Klaibe; and Buffalo Grove produced Brian Arsenau. Had their schools sponsored skating teams such schools as Glenbrook North, Glenbard West, Maine East, New Trier, Evanston, Niles East, and Buffalo Grove might have achieved the same kind of legacy as such skating powers as Austin, Schurz, Tilden Tech, Lane Tech, Taft, and Lindblom achieved during the glorious era of speedskating in Chicago.

Published with permission. All rights are reserved by the author.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Illinois High School Association.