This article originally appeared in the Journal of Sport History,

Volume 30, No. 1, spring 2003. It is reprinted with permission.

Chicago High School Football Struggles,

The Fight for Faculty Control,

and the War Against Secret Societies,

1898-1908

By ROBERT PRUTER

Lewis University Library

Lewis University

"We are determined to kill off the frats and sororities in the high schools and this may delay the work of the board of education two or three years, but we are determined that secret societies must be driven out of the public schools, even if scholars are driven with them." — Otto C. Schneider, President of the Chicago School Board, Inter Ocean, 12 September 1908

"It's a war to the knife now," dramatically declared one of the "frat" men..."The board has no right to say what society we shall or shall not belong to, and we are going to fight." — Inter Ocean, 13 September 1908

During the Progressive Era there was the urge to reform all areas of American society, and the educational sphere was no exception. One of the principal reforms of the educational establishment was the desire to make education available to all. Schooling for all was seen as a means of social reform by bringing the working class and immigrants into the elementary and secondary schools and making the schools broad-based democratic institutions. Such schools would facilitate the Americanization of the population into one melting pot and at the same time ameliorate societal pathologies.1

To achieve these ends, the educational establishment, from 1898 to 1908, carried out three vital reforms that helped shape the American public high school into the institution that we know today. In the most significant of them, educators moved the public high school from being almost solely a college preparatory institution serving a small sliver of the middle and upper classes to becoming a broader educational institution serving a much larger segment of the student population from all types of backgrounds. At the same time, school administrators were in the process of taking control of the extracurriculum, notably athletics, which students had previously been run, and developing student activities into a bonding institution to serve all students. And finally, high school educators in a long war against secret societies (i.e., fraternities and sororities) succeeded during this period in suppressing their activities in the schools and at the same time their domination of the extracurriculum. These three reforms should be viewed as interrelated and in this paper I will demonstrate how in one city, Chicago, they all came together in the educators' fight for control of high school football, and how the public high school culture was thus reshaped to the kind of institution that reflected Progressive Era ideals.

As the public high schools in the United States grew in enrollment 711 percent from 1890 to 1918 by bringing in a population increasingly made up of immigrants and working class students, educators of the day believed that the high school, as a representative of all tax-payers, should embrace all groups in society, that they should be as inclusive as possible and unified in spirit and action by a common ethos of democratic and American values. While this can be interpreted to educate and Americanize immigrant children in a common "melting pot," that "melting pot" should also be viewed as bringing all children together despite diverse social and economic backgrounds. The Chicago Board of Education typified that view when in 1907, while combating secret societies, it wrote: "The American common school system stands for equal opportunities for all pupils to get a preparation for the responsibilities that come with maturity. Any influence that disturbs this equality of opportunity disturbs the spirit and destroys the basic purpose of our common schools."2

In the standard story on how sports have evolved in the high schools, sport historians have asserted that students generally accepted and appreciated the imposition of faculty coaching and administrative control. In 1931, Elbert K. Fretwell, in his Extra-Curricular Activities in High Schools, asserted that "pupils usually welcomed such supervision and coaching because it enabled them to have a better team." The accounts of reform of interscholastic sports in Michigan, Boston, and New York-by latter day sport historians Jeffrey Mirel, Stephan Hardy, and J. Thomas Jable respectively-seem to confirm this standard story. Together they present a picture of students welcoming the reforms and the assumption of control by school authorities, with a minimum of conflict, essentially because their student-run programs were filled with abuses that the students wanted ended as well. In his examination of the Chicago high schools, Thomas W. Gutowski came to the same conclusion in his findings, saying, "for the most part, students welcomed growing faculty control...students went along because faculty involvement gave them things they needed: assistance in raising money, places to hold meetings and contests, offices for school papers, the expertise of teachers who acted as coaches and orchestra leaders, and smoother running leagues."3

Gutowski, it is true, uncovered innumerable examples of students welcoming faculty control of their extracurrular activities, but that transition was not always smooth and not always wholly accommodating on the sports end. The story is more mixed, especially if one considers the existence of fraternities and sororities in the public schools as part of the battle over control of the extracurriculum. While seemingly separate issues, in Chicago they became intertwined, and what took place was a ten-year struggle between the students and the faculty that was fought tooth and nail in the courts, involving decisions that went all the way up the Illinois State Supreme Court. This vigorous student opposition arose from the attempts by school authorities to suppress "secret societies" (that is, fraternities and sororities), a battle that rested on who in the school controls sports and other areas of the extracurriculum, but which ultimately rested on how a public high school should be defined. The fraternities dominated the sports teams and control of the sport activities was intimately tied into their ability to function in the high schools.

The reason why high school authorities found the extracurricula dominated by the secret societies is because the high school students viewed their institutions as junior versions of the elite-dominated colleges, where fraternities and sororities defined themselves in terms of their achievements not in the classroom but in the clubroom and on the athletic field. The secret societies created a powerful and intoxicating culture that dominated college life, with football and the attendant social whirl that surrounded the game as the preeminent activity that shaped this culture. Thus—to the younger brothers and sisters in the high schools—the colleges of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, whose life was shaped the Greek-letter societies, served as the model of what an educational institution should be.4

Chicago was one of the focal points in the nationwide struggle between school administrators and secret societies during the decade from 1898 to 1908. Chicago educational authorities had a particularly difficult and lengthy fight, as compared to other parts of the country, and were prominent in the national campaign to suppress fraternities and sororities. The city also had a vigorous high school football program, upon which drew the protagonists. This paper will show how Chicago-area public high school football program through its various triumphs and travails during this decade served as the primary area of conflict, as well as the most emblematic, between the student and educational establishment in the latter's drive to take control of the extracurriculum and to suppress secret societies. Football is the focus because it was the symbol in the minds of the turn-of-the-century student of what they envisioned their high school to be, and in the fall of every year as the schools reopened, the student battles with the faculty over the extracurriculum and secret societies manifested itself immediately on the football field.

The Chicago metropolitan area near the end of the nineteenth century included the fastest-growing city in the nation, at more than 1,100,000 inhabitants and 185 square miles, surrounded by some of the most prestigious suburbs in the country, notably Evanston, Oak Park, and LaGrange. The city plus these surrounding communities were all located within one huge county, Cook County. . During the late 1880s and early 1890s, the students in the local public high schools-as did students in many other areas of the country—got together to engage in interscholastic athletic competition. Around the sports of football, baseball, and track and field, the Cook County schools formed a loose organization, generally called the Cook County League. As with other high school extracurricula across the nation, these contests were student initiated, student run, and student controlled. 5

Regarding football governance, most Cook County schools during the 1890s relied mainly on either the team's captain or an alumnus to coach. Such a situation left every season something of an ad hoc situation with regard to coaching, as high school elevens searched for recent grads in local colleges to direct the team for the season and often from game to game. The student managers would arrange the scheduling and handle the gate and finances and together would serve as a board of control. However, during the years 1898 to 1908, the school authorities in Chicago and suburbs gradually took control of the interscholastic program from the students. The assumption of control of Cook County League athletics by reformist educators was paralleled in other parts of the country. The earliest reform measures were apparently instituted in Michigan in 1895, when the Michigan State Teachers Association formed the Michigan High School Athletic Association. The formation of the Public Schools Athletic League of New York City in 1903 was both a reform measure to clean up interscholastic sports and an effort to increase sports activity for the public school children. During 1903-07, the Boston schools athletic program was taken over by reform-minded educators.6

Near the end of the 1890s the "Cook County League" was well in place with a fully panoply of sports. But with haphazard growth came abuses, principally involving the use of ringers, and it was obvious that some overarching governing body was needed. This led school authorities to form the "Cook County High School Athletic League" in February 1898, and adopt a constitution for the league. The provisions of this constitution represented the first attempt by Cook County school authorities to take control of athletics from the students. However, the delegates to the meeting on the constitution consisted of equal parts faculty members and student representatives, and the final document was thus a compromise of the power interests of each group.

The constitution placed management of athletics in equal parts with a Board of Control, consisting of one delegate from the faculty of each school, and with a Board of Managers for each branch of sports, consisting of students from their respective schools. The initial proposal in the constitution was that the Board of Control would be in charge of the collection of all funds-dues, initiation fees, and game receipts-and would have the power to determine rules for all contests. However, student opposition forced the reduction of the Board of Control powers to the collection of dues and of initiation fees only, determining eligibility, and to hear protests. The Board of Managers retained considerable power for the students in that it was still the primary rule-making body; it decided the schedules, and retained control of money receipts from the athletic games. The constitution, while solving some problems of athletic governance, laid the groundwork for unfinished business as far as the faculty was concerned and ensured future conflict between the students and the school authorities.7

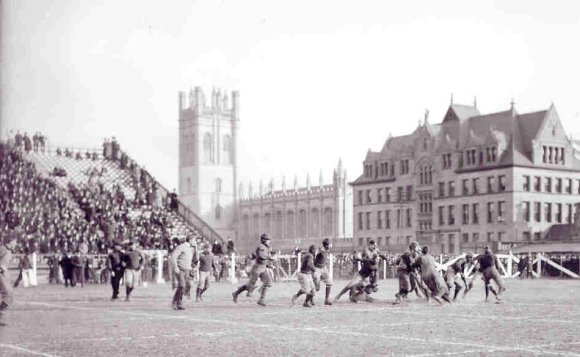

Intersectional Triumphs

The prevailing system of athletic control in the Cook County schools apparently produced extraordinarily successful sports programs, in track and field, baseball, and especially in football. In the fall of 1902 Hyde Park had a team that featured quarterback Walter Eckersall (College Hall of Famer who starred at Chicago), halfback Sam Ransom (famed black all-around athlete who starred at Beloit), and the brothers Harry and Tom Hammond (end and halfback mainstays on Michigan's point-a-minute juggernaut of 1904). Hyde Park ran through the Cook County schedule with lopsided scores, and then took on Brooklyn Polytechnic in perhaps the most one-sided high school intersectional contest of all time. On December 6, at University of Chicago's Marshall Field, Hyde Park slaughtered the Brooklyn boys 105 to 0. There were eighteen touchdowns, which at that time were worth five points apiece. On a snow-covered and slippery field Hyde Park backs made dramatic gains on each down and scored a good percentage of its touchdowns on long running plays. Defense was so formidable that Brooklyn only managed one first down in the entire game.8

Regarding the slaughter, the New York Times dryly remarked, "[the Hyde Park] boys played with their usual speed and circled the Brooklyn ends at will." Coach Oscar C. Aubut of Polytechnic said, "I never saw such fast playing in all my life, and our team was not prepared to meet the open game used by Hyde Park. We have always played a plunging game, and it is much slower." The Hyde Park coach, Lee Grennan, was then hired by Brooklyn Polytechnic to coach their team for the following season. He was never fully appreciated at Hyde Park anyway. The idea of a faculty coach at Hyde Park was a bit new and a bit shaky, and it did not survive the 1902 season. Grennan was the coach during the regular season, but it was the University of Chicago coach Amos Alonzo Stagg who prepared the team for the intersectional match. In subsequent years, Hyde Park relied on an ad hoc system of alumni coaches, while other high school teams in the area adopted faculty coaches.9

In the 1903 season North Division played a tie with perennial power Englewood, and both teams shared the title of Cook County champion. North Division, however, was selected to represent the "West" in New York City in a repeat intersectional game with the New York representative, which turned out to be Brooklyn Boys' High. North Division featured an extraordinarily talented team, notably Walter Steffen (future Hall of Famer at Chicago), Leo De Tray (future All Western at Chicago), and Leslie Pollard (older brother of Hall of Famer Fritz Pollard). The game attracted 5,000 spectators eager to take a look at the fast, open style of play of a Midwestern schoolboy team. They were not disappointed, as North Division totally dominated play, winning 75 to 0, scoring thirteen touchdowns and one field goal. The score would have been even more lopsided had the game not been called on account of darkness with fifteen minutes yet to play. After this massacre New York lost its enthusiasm for intersectional contests against Chicago public school teams, and the series was terminated.10

The disparity in the contests between the Brooklyn and Chicago schools was striking and a bit mystifying. Unlike their counterparts in Manhattan and the Bronx, the Brooklyn schools had as developed a tradition as the Chicago schools in playing football. Since the early 1890s, Boys' and Polytechnic played each Thanksgiving Day for bragging rights to the borough, and were in a well-organized conference, the Long Island League. The newspapers of the day attributed Midwest domination in the contests to the superior open style of play that had developed in the Chicago schools, but that was not the only factor. Both North Division and Hyde Park were loaded with extraordinary talent that included future Hall of Famers and All Americans. So there was a considerable talent disparity as well. The Chicago high schools would never do as well again, and in subsequent years their performance in intersectional contests was mixed at best. 11

Hyde Park vs. Brooklyn Polytechnic Prep, 1902

Englewood vs. North Division, 1903

The 1902 Student Rebellion

While the remarkable achievements of the players on the city's great teams were bringing a lot of attention and acclaim to the level of football played in the Cook County League, there was a war going on for control of the sport. The schoolboy managers retained far too many responsibilities and powers in the eyes of the school authorities, and they began chipping away at them as early as January of 1901, when they drafted a new set of rules and bylaws and took the power of selecting referees and umpires from the managers and placed it in the hands of the Board of Control. Another conflict arose over the power to determine student eligibility to participate, something that theoretically the constitution of 1898 put in the hands of the school authorities. But abuses by the high school teams forced the Board of Control to impose new eligibility standards that required football players to have been enrolled as students within two weeks after the opening of school, and that baseball, indoor baseball, and basketball team members must be enrolled in school at least one month before the first game of the season. A scholarship standard was imposed as well, requiring players to carry at least fifteen hours a week (a full course load), and to maintain a general average of passing. The new rules apparently were so lenient that they elicited no opposition from the students. That would not be the case the following year. 12

During the 1901-02 school year, Superintendent Edwin G. Cooley attempted several times to impose a new scholarship rule, at first a tight one (which the Board of Control did not accept) and then a looser one (requiring a weekly average of 75 percent-i.e. passing grade—in fifteen hours of work instead of an average of 75 percent in each course). This was the same standard that the Board of Control had established the previous year. In the fall of 1902 the Board of Control, under pressure from Cooley, imposed a more rigid scholarship rule that required students who wanted to participate in a sport to have passed every course the previous semester, that is maintaining at least a 75 percent average in every course. 13

The scholarship rule in the fall 1902 season forced one school, North Division, to virtually disband its football team, as some students left to enter private schools. Other schools also lost key players. In reaction, the students rebelled over the immediate issue of the newly imposed scholarship rule, but also over the long-festering issue of the erosion of their control of the game. The students contended, according to the Chicago Tribune, "their teams cannot play under the present conditions, but if the board will go back to its rules of two years ago and annul Superintendent Cooley's rules the trouble will end." The center of the student rebellion was in the one area where they still had some powers, the Board of Managers. The high school managers got together in early October with the intention of forming a new league. One student, on October 3, told the Chicago Tribune, "We are simply going to organize a new high school athletic association which will be under the management of the students and not the teachers, many of whom never saw a football or baseball game and are opposed to the sport." He further claimed that the students had "put up with the Board of Control and their rules long enough," and they would be compelled to withdraw if they were not modified as they were "simply ruining the athletes." He finally pointed out that " two years ago there were big mass meetings in every school just before a game, but it is not so now, for the teams are not representative of the schools, as some of the best men are out of the game, and the board of control does not seem to care. The boys used to manage the affairs and I guess they can do it again." The student managers prepared a plan to set up a new Board of Control, which would consist of a student delegate from each school, and also a faculty and alumni representative from each school chosen by the students. In essence, this plan was designed to return the game to full control of the students.14

The Board of Managers was all set to launch a new league, when Superintendent Cooley suddenly caved in to the threat and granted concessions to the students, by easing the scholarship rule to require only a 75 percent average, or passing, for fifteen hours overall and abolishing the previous-semester passing requirement. Cooley and the Board of Control also partially met the student demands to have a student representative from each school on the Board of Control by permitting two student managers to be represented on the governing body. 15

There were minor instances of rebellion on all levels over faculty supervision that year. In late September the managers tried to book a meeting in a downtown hotel but were thwarted by a Board of Education member who got wind of the meeting and had the hotel bar the "outlaw affair." There was an example of rebellion on the field in November, when Hyde Park captain Walter Eckersall found his role of coaching the team-which he had been doing all season from years of custom—being contested by a faculty coach. Reported the Chicago Tribune, "Capt. Eckersall and Coach Lee Grennan of Hyde Park became involved over a matter of authority last Thursday night, and as a result Eckersall refused to go out for practice last night, claiming his power had been taken from him, but he was finally persuaded to take his place at quarterback."16

Educators also showed heightened concern over the still powerful student managers and their control of the finances in athletic contests, derived primarily from football contests. In 1903, an article by Chicago Englewood High teacher Harry Keeler was published in the April issue of the School Review. In it, he cited a number of triumphs of the Chicago school authorities in governing eligibility of players, adjudication of protests, and requiring students to obtain certification of good health from a physician.17 What remained, he said, was that the faculty must take control of game finances from the student managers. He laid out the situation:

"Many of these boys, who are elected to their position by the members of the teams, or by the athletic association, not because of any special fitness for the position, and who are untrained in affairs of such an important nature, are often called upon to handle and control sums varying from $300 to $1,000, and sometimes even more. Do we realize what burdens are placed upon the shoulders of these managers? Their longest term of office is seldom over three months, during which period they are obliged to meet expense bills of all sorts-equipment of players, traveling expenses of teams, tickets, advertising, use of grounds or halls, police protection, telegraphing, telephoning, postage, etc., and occasionally to report and place in the care of the high-school treasurer (who is not infrequently a student) any surplus."18

Keller further explained the pitfalls of such a system, resulting from incompetence and malfeasance of the student managers, citing particular games involving Chicago high schools. He recommended that teachers assume control of the game finances, and that the school systems institute rules to give the teachers that control. 19

In March of 1904, Superintendent Cooley imposed a new set of rules on the Cook County League, taking back what he had conceded under pressure from the student revolt in the fall of 1902. The two student manager representatives were booted off the Board of Control, and students were required to have passing grades in all four core courses to be eligible to participate. The rules required that there be in addition to the student manager a teacher manager who would oversee all arrangements for games and be in charge of ticket sales, seriously eroding the one area of student control and where a future student rebellion could take seed, and answering the criticisms of the system cited by Keller. Finally, the Superintendent would be given power to suspend a student at any time, a rule the Tribune surmised that was intended to give the superintendent the tools to suppress a student rebellion, like the one that occurred in 1902. An important change in the governance of the league was the assumption of power by the principals; this group demanding the authority to make all rules on eligibility and certain rules on the conduct of games, and Cooley gave it to them. The Board of Control became more of an executive body, enforcing rules made by the Principals' Association.20

The assumption of administrative control over athletics, however, proved to be a far more intractable problem, one that could not be overcome merely by imposing a few more regulations. Underlying and providing the backbone to student resistance was a far greater insidious element, the secret Greek-letter societies, which had taken hold in the schools and had come to dominate the extracurriculum in many Chicago high schools. Most all the athletes on the football teams were fraternity members and it was the fraternities that proved to be most resistant to the imposition of control from school authorities. The battle over the scholarship rule was in reality a proxy battle with the secret societies, the opening salvo in a long war against that element.

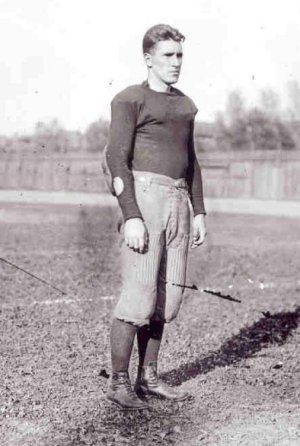

Edwin G. Cooley

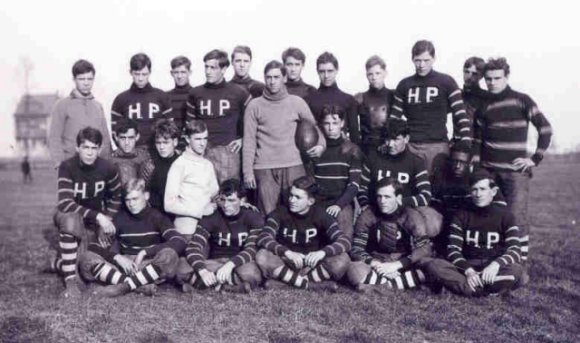

Hyde Park football team, 1902

The Emergence Of Secret Societies

The Chicago school administration apparently thought that it had won the battle for control of high school athletics after its adoption of the March 1904 rules, which was achieved without any visible student resistance. The administration was therefore unprepared for the much more difficult conflict that emerged soon afterwards in May, when the Board of Education launched a campaign to suppress fraternities and sororities in the high schools. On June 22 the Board formerly adopted a rule that attacked membership in fraternities and sororities, touching off a battle that would be waged furiously for five years, as the fraternities and sororities went to the courts repeatedly to obtain injunctions against any enforcement of "anti-frat" rules. The secret societies, made up of the sons and daughters of Chicago's elite, had the support of some of the captains of industry and some of the most influential citizens in Chicago society, and they had plenty of friendly judges who would support their cause. The collateral damage from the war was to severely degrade the football program in the Cook County schools, particularly that of Hyde Park's, which was severely damaged by the Board of Education's campaign. Many top athletes in the Cook County League found themselves on the sidelines.21

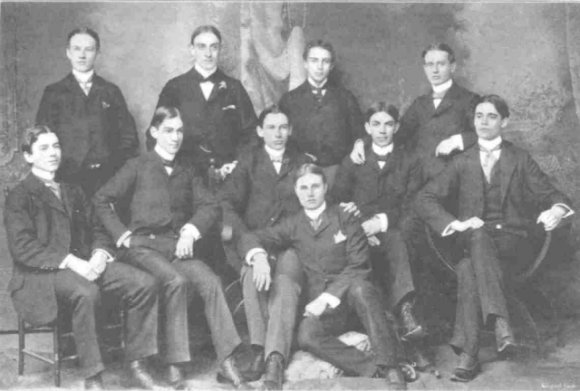

Secret societies first emerged in the 1880s in Chicago high schools, but not until the mid-1890s did the "Greek-letter" society-in imitation of the college secret society—first appear in Chicago high schools. Thomas W. Gutowski, in his 1988 groundbreaking work, "Student Initiative and the Origins of the High School Extracurriculum; Chicago, 1880-1915," estimated that more than fifty secret societies were formed in Chicago high schools from 1880 to 1915. Hyde Park alone had eighteen groups, and another high school had at least sixteen.22

The fraternities and sororities were established in imitation of the college groups; carrying out rush parties to attract students and using secret ballots to choose members (which explains why educators called them "secret societies," since their other activities were most public). The purpose of the groups was purely social, and they selected like-minded students whose social status was presumed equal to theirs. The social status of these Greek-letter groups was clearly upper middle to upper class, and the groups tended to flourish in the more elite Chicago public schools, such as Hyde Park, Phillips, and Lake View. The secret societies held parties, dances, and dinners, published journals, and preened their presumably "elite" status around the school by waving Greek insignia pennants, and wearing rings, pins, buttons, and sweaters bearing their fraternity's or sorority's Greek letter insignia. Fraternities would stage interfraternity contests in baseball and football, outside of the regular high school teams. Some group even maintained chapter houses, either rented or purchased, off the school campus.23

Culturally, the high school version of the Greek-letter society was identical to its college counterpart. Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, in her 1987 work Campus Life, explained that when fraternities took hold in the colleges, they "entrenched themselves in colleges with a strength and intensity that has baffled observers for over a century." Similarly, as we will see, the high school secret societies demonstrated in Chicago the same implacable will to survive. Horowitz showed how college fraternal groups made the extracurriculum their measure of achievement, particularly in sports, and placed themselves outside of the academic standards of achievement. The extracurriculum gave the college undergraduate other standards by which to measure his achievement with his peers, when he could "fight for position on the playing field and in the newsroom and learn the manly arts of capitalism." This world of fraternity culture would potentially establish life-long connections that would help him in his career and establish him in the society he was about to enter. These fraternity men, she remarked, "shaped a student culture of tremendous power." 24

The Chicago high schools of the 1890s and the early part of the next century were considered among the elite institutions of the city. Whereas in the East, the upper middle class or upper class youngster of high school age was sent to one of the elite boarding schools (such as Lawrence, Exeter, or Andover), or attended one of the elite day schools (such as Trinity, Cutler, and Berkeley), in Chicago there was just as good a chance that the boy or girl would be sent to a Chicago or suburban public school, such as Hyde Park in Chicago or New Trier in Winnetka. The Chicago high schools in the mid-1890s were truly for the elite, serving only 6,681 students, or 4 percent of the high school-age population of 174,811. The high school population grew to 9,661 students in 1900 and to 11,208 students in 1904. The Child Labor Law of 1903, which forbade employment of children less than fourteen years of age and regulated employment of those fourteen through sixteen, only mildly affected the high school enrollment in the law's initial years. Thus, such high schools as Hyde Park and Phillips had the same class of people who established the fraternities and sororities in the colleges. With regard to private schools, and particularly of the boarding schools of the East, the educational establishment was generally accepting of fraternities, as they fit in with the away-from-home college model.25

In the East likewise some public school systems appeared to have been more accommodating to the existence of high school fraternities and sororities. In Massachusetts and New York, "some of the older schools" were reported to have found secret societies helpful in the running of the schools (this reference could well refer to such schools as Boston Latin and Brooklyn's Erasmus Hall). In New York City, the public schools reported either minimal involvement of students in secret societies or if there was involvement there was considerable support and sponsorship by the faculty. There was thus little conflict in New York City over the issue of high school secret societies. 26

That the experience of the Eastern big cities was so different can be attributed in part to the large number of private schools that siphoned off the "secret society" types from the public schools. Chicago and other Midwestern cities, likewise, had a plethora of private secondary schools, but relative to the East-for example, where New York City developed no public high schools until 1897- the public high schools were valued more highly there by the middle and upper classes who often preferred them to the private academies and day schools in the area. 27

Thus, in the public high schools in Chicago, as well as most public school systems elsewhere in the country, the emergence of fraternities and sororities in the institutions was met with alarm. Beyond alarm, Chicago high school educators were outright hostile at this imitative collegiate world created by their students. Cook County school superintendent Augustus Nightingale took a typically extreme position, He insisted that high schools should not ape colleges and that to "call these pupils freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors, to encourage class yells and class colors, to espouse the brutality of football, or even to permit the existence of secret fraternities and sororities, are each and all detrimental to the better interests of the growing, adolescent child." He further proclaimed: "These institutions in colleges are an inspiration; in high schools, a menace...[T]hey should be eradicated at all hazards." 28

On the national level, the "frat question," first attracted national attention in 1895, when the subject was discussed at the National Education Association (NEA), but only after the turn of the century did the issue of secret societies fully engage the educational establishment. When Henry D. Sheldon came out with his book, Student Life and Customs (1901), he barely touched on the issue in his chapter on "Student Life in the Secondary Schools," other than to note that in his survey nine respondents condemned them and that in six of the respondent's schools they were permitted to exist. Yet in the following years, The School Review, Education, NEA Proceedings, and other publications of the education establishment all would become fully engaged with the issue.29

The National Education Association only dealt with the problem of secret societies at its forty-third national meeting held in St. Louis, Missouri, in July 1904. There, Gilbert B. Morrison of McKinley High of St. Louis addressed the conclave on the subject, after which the NEA appointed a committee to examine the issue and report back to the NEA the following year. Morrison's report essentially gathered survey results, testimony, and other findings collected locally in Chicago, Washington state, and other locales. What it reported was universal condemnation by school authorities against the existence of secret societies in high schools. Based on the committee's report, the NEA in 1905 passed a resolution condemning secret societies. 30

The School Review, the educational establishment's journal on secondary education, was particularly involved with the issue, publishing letters, reports, court decisions, and research papers. The problem of secret societies was discussed at length in its reports on the conferences of the "Academies and High Schools Affiliating or Cooperating with the University of Chicago." A committee of the conference (appointed in 1902) issued a report in 1904 based on a survey of 306 schools. The report, authored by Chicago principal Spencer C. Smith of Wendell Phillips High (which had a large number of secret societies), found an almost universal agreement from secondary school authorities that secret societies were a damaging presence in high schools. The Review followed this coverage with essays by Gilbert B. Morrison (May 1905) and William Bishop Owen (September 1906), both condemning secret societies; and in December 1906 published the State Supreme Court of Washington decision, which ruled that school authorities have the right to regulate against membership in fraternities and sororities. Other professional journals likewise dealt with the secret society issue, notably in Education and in The Elementary School Teacher. 31

Hyde Park fraternity, 1896

Hyde Park fraternity, 1903

The Objections To Secret Societies

As Chicago was one of the hotbeds in the development of high school secret societies, its school system's experience with the issue was both reflective of the national development and its primary exemplifier. The Chicago objections to secret societies thus mirrored those of education authorities nationwide. Objections were based on assumptions of what a public school education was supposed to represent; that is, a socially democratic institution. Thus, one of the most frequent objections from this era is the "undemocratic nature" of secret societies. A 1904 report from Chicago principals and teachers to the city's school superintendent, Edwin G. Cooley, which helped launch the school system's campaign against secret societies, made exactly these points: "We believe these organizations are undemocratic in nature, demoralizing in their tendencies and subversive to good citizenship;" and "Since the public school is an institution supported by public tax, all classes, without distinction of wealth or social standing, are entitled to an equal share in its benefits. Anything that divides the school community into exclusive groups, as these societies do, mitigates against the liberalizing influence that has made one people out of a multitude." 32

Another frequently observed objection was that members of fraternities and sororities, despite their native intelligence and their upbringing in cultivated homes, tended to neglect their studies to engage in secret society frivolities. The 1904 Chicago report said, "Our experience shows that the scholarly attainments of the majority of students belonging to these secret societies are far below the average, and we have reason to believe that this is due to the influence of such organizations." A 1907 Board of Education report backed up this observation with some hard statistics. At one high school, of the eighty-seven sorority girls in eleven societies thirty were below passing grade; and of the thirty-four boys in five societies, nineteen were below passing average. Of the entire eighty-seven the whole average was 75.6, just .6 percent above the passing mark. Thus, the 1902 conflict over the scholarship rule can be seen to represent the first attack in the war against what was deemed the pernicious influence of secret societies.33

Secret societies were also faulted because they introduced immature high schoolers into a world of adult behavior and mores-encouraging them to engage in adult social habits and class snobbery, and in their vices as well. The 1904 principals and teachers report alluded to this by saying, "They offer temptations to imitate the amusements and relaxations of adult life, while their members have not acquired the power of guiding their actions by mature judgment." A 1907 Board of Education report spelled this out: "...idleness, expense, trivial conversation, indulgence, love of display, and the spread of gossip all go with the fraternity; and that, in the case of some special boys' organizations, we may add to these keeping of late hours, ribald language, obscene songs, smoking, drunkenness, gambling, and social vice." Chicago Tribune editorialist, William Hard, in a national exposé on high school secret societies that drew much of his evidence from the Chicago schools situation, reported in Everybody's Magazine that there were also occasions when high school fraternity houses in the city had been used for evening parties with "women from the Red Light District." 34

The criticism of fraternities and sororities by the principals and teachers that particularly hit home was that they saw these groups as destructive of the community of interest in the high school and subversive to the authority of the faculty. The 1904 report said, "The effect of secret societies is to divide the school into cliques, to destroy unity and harmony of action and sentiment, and to render it more difficult to sustain the helpful relations which should exist between pupils and teachers." The 1906 Board of Education report was more explicit on the subversiveness of secret societies: "They are centers of rebellion against school regulation. They are a self-appointed, irresponsible power in the school, interfering with the free initiative of other students and with the authority of the faculty." 35

Almost as frequently observed was that secret societies tended to dominate the social organization of the school, and take a disproportionate share of the students' offices and dominate the athletic teams. The 1906 report noted, "These secret aggressive groups take an unfair share of the school advantages, and treat the rest of the students as 'barbarians.'" For example, Superintendent Cooley reported on one Chicago high school, where fraternity or sorority members held twenty of the twenty-five elective positions in the school.36

The popular press nationwide echoed these same charges against secret societies, voicing roughly four main concerns: (1) they are inimical to the spirit of democracy and shared community in the high school, dividing the school up into cliques; (2) they encourage immature students to imitate the worst behavior of adults in their shabby snobbishness and frivolities by the girls, and the taking up of vices by the boys; (3) they are inimical to scholarship; and (4) they encourage disrespect to and rebellion against school authorities. The most notable of the articles was William Hard's long piece in Everybody's Magazine, in August of 1909. Chicago Tribune editorialist Hard, along with the editorial writers in all the other Chicago newspapers, had been attacking secret societies in high schools for years, and he laid out the entire case against them in this popular general interest magazine, using many examples from the Chicago School Board experience. The same month, The Century Magazine weighed in with a small feature by Charles A. Blanchard, noting how universal the condemnation of high school secret societies had become. Sororities in high schools were also attacked in the pages of The Ladies' Home Journal in two articles, in September and October of 1907.37

Hyde Park sorority, 1903

The Fight Over School Representation, 1904-1907

The Chicago Board of Education "anti-frat" rule of 1904 did not attempt to abolish fraternities and sororities outright. The intention of the rule was to bar any public recognition for all members of fraternities and sororities-by denying them the use of schoolrooms for meetings, the use of the school name, or by representing the school in athletic and literary contests or in any other "public capacity." The participation in extracurricular activities by secret society members was made contingent on their renunciation of membership in their Greek-letter group, and their discarding of articles of clothing or jewelry with Greek-letter insignia. While educators gave the condemnatory name "secret societies" to fraternities and sororities because of their secret initiations, paradoxically, the educators by their actions were forcing the Greek-letter societies to become more secret.38

The "anti-frat" rule made its most immediate and dramatic impact on the football programs in the schools. Early in the 1904 football season several of the Cook County League schools lost their best players to the anti-frat rule. Hyde Park was the school most affected by the anti-frat rule, but Phillips was affected as well. Both teams lost games to schools that were less impacted by the ban. Suburban member Oak Park was not affected by the Board's ruling-it being a suburban school-but it carried out anti-frat efforts as well, forcing the team captain off the squad because of his fraternity membership. Early on, the Hyde Park and Phillips fraternity students decided on a plan to evade the rule by submitting phony "resignations" to their respective fraternities that they could show their principals, but at the same time secretly continuing their memberships. That approach was rendered moot when parents of four Hyde Park students, among them star player Calvin Favorite, filed suit and obtained a court injunction in mid-October that restored players to the Hyde Park and Phillips teams, considerably strengthening their programs. The court reasoned that if athletic teams or literary societies of the schools are allowed to hold meetings on the school premises and use the school name, then school authorities cannot discriminate against secret societies and they should be legally entitled to the same privileges. The suit would wend its way through the courts for the next four years.39

With the help from the courts, Hyde Park increased its veteran players from one to six. However, the boost the frats gave the team was not sufficient to challenge North Division, which had been only minimally affected by the anti-frat rule and had been practicing and playing with the same members since the beginning of the season. North Division won the title in 1904 but made no one forget the glory years of 1902 and 1903. Throughout the remainder of the school year, the injunction remained in place and was in place when the Board published its annual report in June of 1905. 40

The Cook County League was divided into two geographical divisions for 1905, and the winners of each met at the end of the season. Hyde Park, with its usual complement of fraternity men, met a non-competitive Crane Tech team for the league championship, beating them 58 to 0. The Board of Education throughout the 1905-1906 school year attempted repeatedly to enforce its anti-frat rule, and repeatedly was thwarted when parents of fraternity members went to the courts to impose injunctions. In March of 1906, the Board got the court to lift the injunction, and in May attempted to restore its ban on secret societies by deciding anew to enforce the 1904 rule. Once again the parents went to court and obtained an injunction restraining the Board to the end of the spring semester. An impatient Chicago Tribune editorial writer, probably William Hard, chided the board in mid-May, "If the Board of Education had been more in earnest this subject would have been disposed a year and a half ago. It would not have allowed itself to be played with and made ridiculous by some fraternity schoolboys who have coaxed their fond parents into hiring lawyers to get injunctions. If the war of the board on the high school fraternities is a mere sham war the sooner it is dropped the better, for it is becoming tiresome." 41

In late November of 1906, the Board of Education was able to restore the ban. While in the previous year, perennial athletic power Hyde Park was able to hold off the Board the entire season through court injunctions, its 1906 football team in the last two scheduled games was hard hit with the loss of key players-particularly its captain, Eberle L. Wilson. The Inter Ocean noted in Hyde Park's next-to last game, a loss to Oak Park, that, "Hyde Park was weakened by the anti-fraternity rule, through which four of its strongest men were placed on the ineligible list." In the last game with Englewood, the Hyde Park team chose not to appear. The Hyde Park parents had returned to the courts to restore the injunction, but the season had come to a close. They then continued their cause by filing a suit—Eberle L. Wilson v. Board of Education of the City of Chicago—to prevent the Board from enforcing its 1904 anti-frat rule. The suit would eventually be taken up by the Illinois Supreme Court and would ultimately represent the final defeat of the supporters of secret societies.42

During the 1906 and 1907 seasons of football competition, the football league was in disarray, and reverted back to the days of essentially student control. In June of 1906, a joint committee of the Board of Control and the high school principals voted not to award a pennant for the coming football season. The Chicago Daily News reported, "For some time there has been a feeling among school principals that football should be suspended for at least a year." That feeling probably came from a culmination of factors-the violence of the sport (Oak Park player's death the year before probably came to mind), the constant struggle against the fraternities that wore on the administrators' resolve, and the continual resistance by the fractious students against faculty control. There was an overall sense of "Let's wash our hands of this mess," as reflected by the fact that although there was no injunction in effect the 1904 ban on secret societies was not being enforced.43

While recognizing that the committee's decision did not directly abolish football, the Daily News predicted that "it means practically the death of the game." Yet the paper did not count on how deeply rooted the sport had become in the fabric of the city's schools. In September the principals allowed the students to form teams; the Inter Ocean reporting that the principals were, "willing to let the boys play if they wish to," indicating the degree by which students still were making decisions beyond faculty control. The only area of faculty control was in their retention of determining eligibility. As the students began to organize teams, the newspapers continued to recognize the existence of a "Cook County" championship series, and the ad hoc league-called the High School Association-worked out a round robin weekly schedule of competition. The essentially student-run league was not fully respected though, and the season was somewhat in disarray as the scheduling became ad hoc. Some schools formed "outlaw" teams against faculty wishes, such as Crane playing under its old name of "English High," and McKinley playing under its old name of "West Division." The adoption of the old names was an assertion of student rebellion.44

The level of football apparently did not suffer from the league's disarray. The 1906 season saw the introduction of a new open game of football as a result of the national reform of the rules implemented by the colleges following the 1905 season that were designed to make the game less brutal. Despite the battle raging between the students and the school authorities, the students and coaches were attuned to the changes in the football rules and adapted with remarkable facility. The Chicago Tribune reported in early November on a University High 5 to 4 defeat of Hyde Park: "The new game was played brilliantly by both teams. Forward passes, onside kicks, long punts, and wide end runs made the contest spectacular in the extreme. There was little semblance to the old style game even among the high school boys." In another match-up, Rockford with successful forward passes beat West Division, which threw unsuccessful forward passes.45

The Cook County championship game between North Division and Oak Park, in which the former prevailed 22 to 9, was described by the Inter Ocean as a "good demonstration of reformed football, and the play was fast, with no rough work and no man on either side compelled to retire from the field. The schoolboys demonstrated that they had applied themselves to a thorough study of the new rules. The forward pass, the onside kick, quarterback runs, and the end runs were tried and executed with remarkable ability." In North Division's drive for its first touchdown two forward passes netted 40 yards. 46 What undoubtedly contributed to the football season's vitality was the continued membership on the teams by fraternity members through much of the season.47

Nonetheless, when the 1907 season began with the formation of a "new league," several newspapers commented negatively on the previous season. The Chicago Record-Herald explained, "[T]he new league closes a chapter of high school football management that the lads are not proud of. Last season, as an experiment, the board of control decided to let the Principals' Association run the sport. The association paid little if any attention to the teams, letting the managers do about as they pleased." The Inter Ocean stated, "[T]he action of the Board of Control last year in refusing to allow the formation of the usual league had a dampening effect on the spirits of the majority of football enthusiasts." Clearly, the 1906 by-default schoolboy-run league did not succeed in the eyes of many; the feeling was that a faculty-run league would be superior.48

Football in the 1907 season again saw no league competition sponsored by the Board of Control and the league continued in disarray, with the problem of dealing with exclusion of fraternity members on several teams. Hyde Park and Phillips each presented teams with virtually no football experience, as all their players from the previous year were barred from participating; the circuit court before the season had given the Board the green light to enforce its 1904 anti-frat rule. The extent to which fraternities dominated athletic competition in these years is most revealing from the Hyde Park situation. In a pre-season football report, The Inter Ocean commented that, "The anti-fraternity rule will be noticed at Hyde Park, and it is possible that the school will not be represented by a team. The prominent athletes at Hyde Park are nearly all fraternity men, but the past year has developed many promising performers among the 'barbarians.'"49

The 1907 season was initiated when the head of the Principals' Association, Dr. Charles E. Boynton, called on the team managers to come together in late September to form a league and draw up a schedule. Five schools answered his call-Hyde Park, Englewood, Phillips, Crane Tech, and North Division. Boynton appointed an advisory board for what was a largely a league run by the student managers. The organization was called the "Cook County High School Football League." Oak Park chose not to compete against the city schools, contending that it would not participate in the "outlaw" league, apparently considering any organization outside control of the Board of Education to be illegitimate.50

As in the 1906 season, the football league was shaky from the start. North Division's football program was facing stiff opposition from the school's faculty, and, following an opening-day loss to Hyde Park on October 19, was forced to disband after it was discovered using ineligible players. Subsequently, the players with impunity continued to compete against private clubs under the name of the "North Division Athletic Club." In late November the principal of North Division withdrew his school from all athletic activities for the entire year based on a record of infractions in various sports dating back to the previous year.51

On November 23 when Hyde Park and Crane met at Marshall Field, it was for the Cook County title according to the Chicago Record-Herald, Inter Ocean, and the Chicago Daily News. The game ended in a tie, leaving an unsatisfactory state of affairs, but a Crane defeat at the hands of Englewood several days later allowed the newspapers to recognize Hyde Park as the champion. The Chicago Tribune, probably deciding not to give the "outlaw" league any credibility, dubbed the Oak Park-University High match on November 28 won by Oak Park as the Cook County championship game. However, Oak Park did not play one city school the entire year. Note what was going on here. The newspapers were conferring championship status, while the essentially student-run league was impotent to make a decision.52

In November of 1907, the Illinois Appellate Court affirmed the decision of the Superior Court of Cook County in the Eberle L. Wilson suit, filed by the parents of four Hyde Park students a year earlier. What was at issue was the Board's right to bar fraternities and sororities from representing the school and using school facilities. The court ruled against the parents and said that the school board did indeed have the power to bar secret societies from using the school name or the school building, and to prohibit fraternity members from representing their school in any literary or athletic contest, and that there was no natural and inalienable rights under the constitution for the students to engage in such contests. The Chicago Tribune wryly observed in supporting the court's decision, "The public schools were not instituted primarily for the purpose of engaging in interscholastic athletic contests," scathingly denouncing fraternities as "potent factors for evil."53

Phillips High School football team, 1906

War of Extermination

Emboldened by the appellate decision in the Wilson case, Chicago school authorities in January of 1908 stepped up their anti-frat campaign. They expected that the State Supreme Court would eventually affirm the decision of the Appellate Court. Otto C. Schneider (the president of the Board of Education) and Edwin G. Cooley (the Superintendent of Schools) declared a "war of extermination" against fraternities and sororities. They felt they now had the power to deny secret societies public recognition, and were free to pass even more stringent rules against secret societies, by banning membership altogether and promising to "make membership grounds for expulsion." The school authorities' position was strengthened even more on March 5, when the Illinois Appellate Court upheld the Board position in the Calvin Favorite suit filed by parents of four Hyde Park students in the fall of 1904. The court merely cited the Appellate opinion in the Wilson case in deciding the Favorite suit.54

On March 11, the Board of Education met to pass a rule outlawing all fraternities and sororities. With some thirty sorority and fraternity members looking on, they passed a rule banning student membership in secret societies, beginning September 1, 1908, after which such membership would be punished with suspension. The board required that entering students had to sign a pledge that they were not a member of a secret society and had no plans on joining one, and refusal to sign was grounds for suspension. As the president announced that the rule had passed, "the lips of several of the [sorority] girls trembled and tears trickled, unheeded, down their cheeks. Then they rose and left the room quietly."55

Finally, on April 23, 1908, in the most decisive` case in the Board's long struggle against secret societies, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Board in the case of Eberle L. Wilson v. Board of Education of the City of Chicago, affirming the lower court decisions. The Supreme Court concluded its decision, commenting on the Board's 1904 anti-fraternity rule:

"The rule denied to pupils who were members of secret societies no privilege allowed to pupils not members, except the privilege of representing the schools in literary or athletic contests or in any other public capacity. They were not denied membership in associations of pupils of the schools for literary, social, musical or athletic exercises, and were not prohibited from receiving the same benefits from those organizations that pupils not members of secret societies received. They were only prohibited from representing the schools as members of those associations, in public contests and capacities. This was not a denial of any natural right and neither was it an unlawful discrimination." 56

Despite all the setbacks in the courts and the impending Board ban on secret societies in September, the fraternities and sororities remained defiant. In July 1908, at the national convocation of the Gamma Sigma Fraternity, which had chapters in Oak Park, Evanston, Hyde Park, and University High, the president of the fraternity announced, "The Gamma Sigma Fraternity instituted the fight against the Board of Education, and we intend to carry it to a conclusion." When the schools opened in early September, authorities moved to get signed statements from some 800 secret society members in the schools (out of a total high school population of 13,000) renouncing their memberships under threat of expulsion. On September 11, at Hyde Park High, 51 defiant students were expelled, and when they tried to enter the school on September 14 they were escorted out of the building. The same day, some 25 representatives of 18 fraternities and sororities met with alumni to plan strategy and form the Inter-Fraternity Protective Association. A defense fund of $1,000 was started, with the intention of increasing the amount to $25,000. The lawyer they retained, John C. Wilson (the father of Eberle L. Wilson), went to court to file a suit against the board on behalf of a Hyde Park student, Edward M. McDonald. The Chicago Record-Herald reported on an alumnus of Hyde Park, who bragged that "the sons and daughters of several millionaires were among those suspended yesterday from the Hyde Park High School," and the Inter Ocean noted that the combined wealth of those parents was $15,000,000.57

There would be no more injunctions. On October 3, in the Circuit Court, Judge Windes after hearing the McDonald case ruled that the Board had the power to ban secret societies under their right to impose regulations, and that there were no rights in the state or federal constitutions violated by the regulation banning secret societies. The Board attorney told the Chicago Tribune, "This ends fraternities and sororities. They lost in the other fight and they lost this one. The Appellate and the Supreme courts will undoubtedly sustain Judge Windes. Even it they amend the petition I do not see how they can make out a case in view of what the court has said."58

The victory of the Chicago Board of Education over the secret societies, following favorable court decisions, paralleled similar anti-frat victories across the country around this time. The states of Minnesota, Indiana, Ohio, and Kansas all enacted laws that banned high school fraternities, and a myriad of school boards across the country-notably in Seattle, Washington; Springfield, Massachusetts; Meriden, Connecticut; Brooklyn, New York; Indianapolis, Indiana; and Louisville, Kentucky—successfully put bans into affect. Reflecting the experience of Illinois, school board bans in Washington and Minnesota were upheld by the state supreme courts.59

Despite the aggressive opposition mounted by the pro-fraternity forces, the 1908 football season was conducted under a successful ban on fraternities; the parents' suit never went anywhere after their defeat in the circuit court. With the successful suppression of the fraternities, school authorities felt comfortable in restoring institutional control over the football program. The Board of Control thus reimposed its control over the Cook County League, becoming sponsor of the competition.

Epilogue

The 1909 football season was the first peaceful one in years. There were no reports of fraternity and sorority member expulsions, and no reports of frat football players attempting to regain their status on the team. Opening day of the school year was a remarkably quiet one, signaling the end of open resistance by the fraternities and sororities. Freed by the courts to make regulations, the Board of Education's subsequent campaign against the secret societies could be likened as being reduced to a guerrilla conflict-the enemy appearing and disappearing, seeking to evade direct confrontation but continuing to skirmish and undermine authority. Thus, in later years the Board tweaked the rules to make them ever more effective in rooting out the secret societies. During the 1909-1910 school year, the Board made the penalty more severe for secret society membership, by changing the penalty from suspension to expulsion. The fraternities and sororities during the year went underground, carrying out initiations and activities at members' homes.60

The Board revisited the secret society ban in 1911, 1912, and 1913, stiffening the rules each time. In January 1913, the board suspended some 200 students in a clampdown on secret societies. By January 1915, the Board had in place its most stringent rule ever, requiring permanent expulsion of secret society members from the school system, barring them admission to any public high school in Chicago.61

In the suburbs, the battle against secret societies continued as well. For example, at Oak Park High, in the western suburb of Oak Park, under the school board's rule against secret societies, the school in 1912 expelled a student for being a member of a fraternity. The parents of the student sued, and persuaded an Illinois district court to restore the student to classes at the school in March of 1912. However, an Illinois appellate court held up the right of the school board to "legislate against student secret societies." The local Oak Park paper noted: "it is believed that the appellate court's findings will just about settle the frat problem in Illinois." And it just about did.62

Although fraternities and sororities were never completely abolished in Chicago-area high schools, by 1909 they had ceased to be a disruptive force, stripped of their power to dominate the extracurriculum. By World War I, school authorities with successive regulation had succeeded in forcing them completely underground. Thomas Gutowski likened the situation to a truce, the principals unable to exterminate the fraternities and sororities and prevent their participation in school activities, and the secret societies no longer on display and dominating school life. The administrators in reality had won the war, as they effectively destroyed the power and cachet of secret societies so that they no longer had the ability to parade their reputed "in-group" social superiority before their fellow students. Chicago high schools no longer had a secret society problem.63

High school fraternities and sororities remained a minor issue for decades afterwards. For example, a questionnaire study was made in 1931 of 171 school systems nationwide, and in 101 of them fraternities and sororities were specifically forbidden by state or local rules. But Fretwell in his Extra-Curricular Activities in Secondary Schools, published the same year, barely touched on the subject, and was somewhat blasé about secret societies being a problem, noting, "Where there is a club for every pupil and a wise faculty member for every club, high school fraternities and sororities tend to approach the vanishing point." Fraternities were still operating in Chicago area schools as late as the 1960s, but operating so completely underground it made little difference to authorities whether or not they existed. 64

Eberle Wilson

Conclusion

The great reforming impulse of the Progressive Era produced a nationwide decade-long campaign, from 1898 to1908, to purify its public high schools of fraternities and sororities. The students of the fraternities and sororities saw their high schools as elite institutions that should slavishly imitate the collegiate world of the day. School authorities, on the other hand, saw the twentieth-century high school as an institution to be reformed into a Progressive ideal—an institution that represented all social and economic groups and that reflected an inclusive common democratic heritage of the country. Students did not succumb to the anti-fraternity campaign passively, but fought back vigorously, from mounting protests in the streets to making an aggressive use of the courts to void the authority of the school administrators.

In most respects the anti-fraternity campaign in Chicago typified that being conducted nationwide. Educators in Chicago in tune with their counterparts across the land saw the fraternities as inimical to the type of democratic high school they envisioned for a melting-pot United States and fought them vigorously using a rhetoric that evoked democratic and Progressive ideals.

The Chicago experience, however, appeared to differ from that of the national scene in one key respect. Whereas in other areas of the country, the conflict over control of the extracurriculum and the conflict over the existence of fraternities were parallel developments in the school system, in Chicago the campaign against fraternities became enmeshed in a long-running conflict between the students and faculty over control of athletics, particularly football. The Chicago school administrators' drive during 1898 to 1904 to take over the sponsorship and regulation of high school sports might have triumphed sooner and easier—as similar campaigns did in Boston, New York, and other cities-had not the conflict over fraternities arisen. Only with the expulsion of the fraternities (and sororities) from the Chicago schools in 1908, was the door open for school authorities to reassert their control over the football program, a control they had conceded to the students during the 1906 and 1907 seasons.

While the administration of the football program suffered under student control, the quality of the game seemed not to, as evidenced by the intersectional successes of 1902-03 and the rapid adaptation to the new open-game rules in the 1906 season. This should not be surprising, as football's most avid and devoted players came from the fraternities. School authorities in other parts of the country apparently did not experience this level of resistance on the issue of student control of athletics, but decidedly did on the issue of fraternities.

These are somewhat speculative assumptions given the sparse level of study on interscholastic sport history. The prior examinations by sport historians on the development of interscholastic sports governance in New York, Boston, and Michigan show no recognition of an anti-fraternity campaign at this time, although it is clear this was a nationwide problem at the time. Thus, from the absence of any mention of anti-fraternity campaigns by these historians, one could possibly conclude that perhaps such campaigns, unlike in Chicago, had no direct relevance to administrative attempts at faculty control of athletics. New York experienced a conflict between school authorities and students with regard fraternities, but that the conflict in no way impeded the assumption of control over sports by the faculty.

On the other hand, we do not know exactly what transpired in such states as Minnesota and Washington, where the fraternity problem in the high schools were probably as acute as that in Chicago. Possibly the experiences of educators there might have been closer to the Chicago situation. Thus, what this study has uncovered about the Chicago experience-notably where the fortunes of the football program became intertwined in an anti-frat campaign—invites exploration by sport historians of interscholastic sports in other areas of the country where the conflict was similarly severe.

In any case, what is evident is that from 1898 to 1908, the public high school system nationwide experienced three vital reforms-the broadening of the student body, the suppression of fraternities and sororities, and the assumption of administrative control of athletics—in communities big and small, rural and urban. Because school authorities ultimately prevailed, today the American public high school, although not representing the ideal institution as envisioned by the early twentieth century educators, is much the better with the absence of Greek-letter societies and the end to student-run football games. And in concordance with the Progressive Era understanding that school reform leads to broader social reform, American society has come out much better as well.

Notes

1. This is the standard "melting pot" explanation given for Progressive Era reform as exemplified in the work of Lawrence A. Cremin in his chapter, "Culture and Community," in The Transformation of the School: Progressivism in American Education, 1876-1957 (New York: Knopf, 1961), 58-89. See also Ellwood Cubberley, Public Education in the United States: A Study and Interpretation of American Educational History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1934): 502-504; and Ira Katznelson and Margaret Weir, Schooling For All: Class, Race, and the Decline of the Democratic Ideal (New York: Basic Books, 1985): 96-99.

2. Joel Spring, The American School 1642-1985: Variations of Historical Interpretation of the Foundations and Development of American Education (New York: Longman, 1986): 152-153. Spring cites Ellwood Cubberley's work from 1919 as being representative of this "altruistic" view of the role of the high school, although the reports and articles by educators in the first decade of the twentieth century are suffuse with such views. See for example, Gilbert B. Morrison, "Secret Fraternities in High Schools," National Education Association Journal of the Proceedings and Addresses of the Forty-Fourth Annual Meeting (Winona, Minn.: National Education Association, 1904), 488; and F. D. Boynton, "Athletics and Collateral Activities in Secondary schools," National Education Association Journal of the Proceedings and Addresses of the Forty-Fourth Annual Meeting (Winona, Minn.: National Education Association, 1904), 206-207, the latter which argues that the extracurriculum could serve as a melting pot to instill democratic and American values. This observer largely accepts the "altruistic" understanding of the function of the American high school but notes that there are historians who argue that the words of the educators are mere "rhetoric," masking social and political "reality." Thus, there are a variety of views that see the Progressive Era educators as reforming the schools with the intent of imposing "social control" over the students. Three significant social control theories see the high schools in the 1890-1915 period as: 1) being designed to provide workers inculcated with capitalist values to serve the "interests of the owners of industrial enterprises"; or 2) to provide students inculcated with the sense of cooperation and national spirit to serve the interests of the "corporate liberal state"; or 3) to prepare the nation's youth as "future soldiers." See Spring, The American School, 152-154; Timothy P. O'Hanlon, "School Sports As Social Training: The Case of Athletics and the Crisis of World War I," Journal of Sport History 9 (1982): 7-29; "Secret Societies in the High Schools," Fifty-Third Annual Report of the Board of Education for the Year Ended June 30, 1907 (Chicago: Board of Education, 1907), 132 [QUOTATION].

3. Elbert K. Fretwell, Extra-Curricular Activities in Secondary Schools (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1931), 409; Jeffrey Mirel, "From Student Control to Institutional Control of High School Athletics: Three Michigan Cities, 1883-1905," Journal of Social History, 16 (Winter 1982): 94, noted that in, "no student publication was the end of the student-run athletic associations lamented or denounced." Steve Hardy, in How Boston Played (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1982), 119-120, related that, "only after continued prodding and complaining (sometimes by the students themselves) of the growing evidence of abuses and cheating did the administration enact reform and regulation from above." The issue of student resistance to reform in New York did not even make it on the radar screen of one researcher on New York high school sports. (J. Thomas Jable, "The Public Schools Athletic League of New York City: Organized Athletics for City Schoolchildren, 1903-1914," The American Sporting Experience, edited by Steven A. Riess [Champaign, Illinois: Leisure Press, 1984], 226. Jable stated concerning teacher involvement in the new program that it "certainly enhanced teacher-pupil relations." The source on Gutowski's remarks is Thomas W. Gutowski, "Student Initiative and the Origins of the High School Extracurriculum, Chicago, 1880-1915," History of Education Quarterly 28 (1988): 70-71. This researcher owes a debt of gratitude to Gutowski to alerting me to the war over secret societies and other issues related to the extracurriculum in Chicago schools; however, I will depart somewhat on his understanding of the level of student opposition to assumption of faculty control.

4. Sport historians have long recognized that in the American university system there exists a variety of student cultures. The names and categories of these cultures tend to vary from researcher to researcher, but the cultures of collegiate, academic, vocational, and the rebel seems to approximate the most common categories. While the academic and vocational student focused their energies in college on the course work, and the rebel student was disinclined to engage in typically collegiate activities or standard classroom work, it was from the collegiate student where college sports arose and where it is best sustained today. In the world of the collegiate student one can find the potent combination of fraternities and sororities, the social whirl of parties and frivolities, and sports and other extracurricular activities, all which makes college a place of social development rather than a place of academic or vocational growth. The collegiate culture has been examined historically by Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz and contemporaneously by Murray Sperber. (Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Campus Life: Undergraduate Cultures From the End of the Eighteenth Century to the Present [New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987]. Sperber, while not trying to do the same thing, in effect brings Horowitz's study up-to-date in his part-diatribe and part-careful analysis and research study: Beer and Circus: How Big-Time College Sports Is Crippling Undergraduate Education (New York: Henry Holt, 2000). Sperber built his study on the earlier work by sociologists Burton Clark and Martin Trow, "The Organizational Context," in College Peer Groups: Problems and Prospects for Research, edited by Theodore M. Newcomb and Everett K. Wilson (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1966), 17-70.

5. Harold M. Mayer and Richard C. Wade, Chicago: Growth of a Metropolis (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1969), 176-178.

6. Mirel, "From Student Control to Institutional Control," 90-94; Jable, "The Public Schools Athletic League," 219-222, 226; and Hardy, How Boston Played, 118-19. Gerald Gems has cited in Windy City Wars (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1997), 98, that the Interscholastic Athletic Association of Illinois, formed in 1893, represented early adult control over high school sports in Illinois, but it was essentially a student-run organization designed to assist the University of Illinois in governing the state high school track and field meet, and did not involve school administrators.

7. "Athletics," The Echo (Medill High School), February 1898, 14. "High School League Formed," Chicago Tribune, 5 February 1898.

8. "Hyde Park 105, Brooklyn Poly, 0," Chicago Tribune, 7 December 1902.