Early Phillips High School Basketball Teams

By ROBERT PRUTER

Black prominence in Chicago basketball dates back to the very beginnings of the boys' game around the turn of the century. In 1901, the very first Cook County League championship basketball team, Hyde Park, featured an outstanding black athlete, Sam Ransom. In his four years at the school, Ransom also led Hyde Park to two Cook County football championships, one mythical national football championship, one Pennsylvania Relays mile championship, and two Cook County baseball championships. Ransom went on to Beloit College, where he played basketball with great distinction.

With the advent of World War I, Chicago like many northern cities experienced the first wave of the "great migration," where tens of thousands of blacks migrated north from the rural segregated South to enjoy the thriving job opportunities opened up by the war boom. Between 1916 and 1919 some 50,000 blacks moved to Chicago, creating two large settlements on the south and west sides. Phillips High was impacted by this migration, being transformed from a virtually all-white school to two-thirds black by 1917. Racial conflict boiled up in the high school and in the city. During 1917-1921, there were 58 racially-motivated bombings in the city. In 1919, Chicago experienced one of the worst race riots in the history of the North.

By 1922, Phillips was virtually 100 percent black, and newspapers began routinely referring designating its athletic teams as "all-colored," as they had routinely referred to the individual black athletes by their color. In basketball, Phillips achieved particular prominence and produced many highly talented basketball players who later achieved fame in college, semi-pro, and professional teams. Its football teams were not as successful as its basketball teams, but the Chicago Defender regularly championed Phillips teams and individuals in all sports as being representatives of achievements of the race.

Basketball was given the most attention in the black press, as it was flourishing in the black community during the 1920s. The high school was far from the only incubator of basketball talent in the community. Larry Hawkins, a black sports history authority and former coach at a state championship team from Chicago, Carver, told the Chicago Sun-Times that Phillips, the Wabash YMCA, and the South Side Boys' Club formed a "golden triangle" to produce great black basketball talent.

In the 1920s and 1930s most high school programs were not divided into varsity and frosh-soph divisions but rather into heavyweight and lightweight divisions. By 1922, when the Phillips heavyweight team won the Central Division title in the Chicago Public High School League, the Chicago Defender had adopted Phillips as the black community's high school. Thereafter, as Phillips High went from success to success during the decade, the newspaper's headlines got higher, the stories grew longer, and the photos ballooned up larger. Phillips' emergence as a black school, however, brought a degree of social conflict at the games with the white schools, and racially-motivated slights and injustices directed at the Phillips teams and fans did not go unnoticed by the Chicago Defender.

Racial tension was ever present during the decade and open conflicts with other Chicago schools erupted almost yearly. When the 1922 team lost to Lane Tech in the semifinals, the paper complained that the Lane supporters arrived early and took all the seats on the main floor, and then Lane ushers, would meet the incoming crowd and yell, "Upstairs, all you Phillips students." In January 1923, there was a particularly ugly clash between student supporters of the Phillips and Lindblom teams. In March the Chicago Defender decried the officiating that allowed Marshall to win a close game against Phillips by repeatedly fouling Phillips players most blatantly, "souring the fair-minded public." The Defender readers knew what "public" was being referred to, and the subtext of racial bias being at work did not need to be articulated.

The Phillips teams were not wildly successful in 1923, but that year introduced a new tradition to the program, the annual banquet given to the Phillips basketball teams by the Chicago Defender. Businessmen, professional people, and representatives of various black clubs, the Y.M.C.A., and fraternal organizations all attended to show their solidarity to their basketball representatives in the Chicago school league. The Defender in lauding the need for the dinner, commented, "The first time in years the old spirit that existed there when 97 per cent of the students were white is back and we all know the complexion of the school has changed owing to the majority of the people in this ward being those of our own."

The Phillips heavyweight team of 1924 received extensive coverage by the Chicago Defender, which felt that the team was destined to win the city championship. Three players on the team--Tommy Brookins, Lester Johnson, and Walter "Toots" Wright-eventually became members of the Harlem Globetrotters. The three, along with teammate Eugene Eaves, after graduation in 1925 formed a semi-pro team, the Savoy Big Five. The team toured the Midwest, and eventually it was taken over by Abe Saperstein and renamed the Harlem Globetrotters.

Much to the dismay of the African American community, this richly talented Phillips team was smashed in the title game by Lane Tech, 18 to 4. While the Chicago Tribune made no comment on the officiating, the Defender reporter, the well-respected Frank Young, felt the referee broke the morale of the team with many foul calls on the Phillips boys and none on the Lane Tech boys. Interestingly, Lane's high scorer in that game was a black player, William Watson, and the Chicago Defender did not fail to point that out. The year 1924 saw Phillips start a new tradition of playing a postseason game with a notable opponent from a distant city. The team in late March went down to Kansas City, Missouri, to play Lincoln High, which they beat 23 to 13. Then in late April the team traveled to Washington D.C., and easily defeated long-time power and previously unbeaten Armstrong High, 17-10. With many of the same players the next two years, the Phillips heavyweights managed to reach the semifinals both times before losing to Englewood.

The ever-present racial tension boiled over during the 1925 season, with clashes erupting at games against Lindblom and Hyde Park heavyweight games. Just prior to the playoffs in February 1925, the principal of Phillips was forced by league authorities to withdraw his team from further competition. The school was forced to play the remainder of year in the segregated black basketball world. The Chicago Defender sponsored the trip of Armstrong High from D.C. to play Phillips in Chicago. Although Phillips had a lost a couple of league tilts, the strength of the Phillips team relative to that of its Eastern rivals was evident in its manhandling Armstrong 25-15. The game drew 4,500 fans. The Fifty-five box seats at the Eighth Regiment Armory were filled with the "elite of Chicago's social and business world." Phillips brought in its 54-piece band as well as its booster orchestra. The Defender devoted a lot of real estate on two pages of its broadsheet to cover the game, and in a throwback to the Thanksgiving Games college football coverage of the 1890s, a separate article on what members of society came to watch the game. The contest was a huge event in the black community, but the mainstream newspapers at most only minimally mentioned the contest.

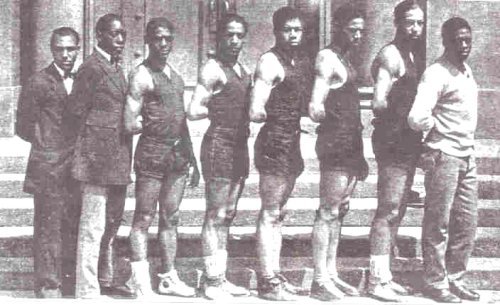

Phillips basketball team, 1925

The heavyweight team of 1926 continued to developed ties with the segregated black schools of the South and East, notably bringing Central High from Louisville on New Year's night. Phillips beat Central and took home the Robert S. Abbott trophy, named after the owner of the Chicago Defender, which sponsored the contest. The paper gave the game extensive coverage, treating the contest as a major happening in the black community. After the game, fans "danced to the music of Dave Peyton's Knights of Syncopation to the wee hours of the morning." Both the lightweight and heavyweight teams were less than stellar in 1926, both being eliminated in the semi-finals by Englewood. The next night at the Eighth Regiment Armory the heavies lost to the state Catholic champion, Peoria Spalding, and the lights beat north side power Schurz. The 1927 heavyweight team had to forfeit all its games, when it was determined that the school had an over-aged player (he was past 20 years old) on the squad. In 1928, the heavyweight team faced such hostility from the predominantly white schools that Englewood and Lindblom purposely played to a tie game to keep the Phillips team out of the playoffs.

The commercial world of professional athletics was an ever-present enticement that occasionally brought trouble to the school's program. The 1925 heavyweight team saw two members of the team, Tommy Brookins and Randolph Ramsey, face recruitment by the Eighth Regiment semi-pro team, and the Chicago Defender wrote an editorial warning the boys off from joining. The 1927 team that had to forfeit its games because of an over-aged player, had another trouble that year, and would have had to forfeit its games anyway for playing a semi-pro team in Cleveland, Ohio, during the season.

A Chicago Public High School championship finally came to Phillips in 1928, when its lightweight team destroyed a fine Harrison team, 23-10, to win the title. The team, typically, experienced at least one disturbance at one of its games, against Hyde Park in February, when students poured out of the stands in a melee after a Phillips player, star player, Al Pullins squared off against a Hyde Park player. It also experienced an attempt by some white principals to "rob" the team of its position in the championship game, when some of the principals suggested that the Phillips teams be included in a special playoff of three North Side teams who were deadlocked in a tie. This first all-black championship teams opened a lot of eyes in the city. Said a Tribune reporter, whose comments would be echoed a quarter of century later by observers of the 1954 DuSable teams: "Speed that was dazzling, accurate shooting that was almost amazing, and a stout defense that thwarted Harrison." Well, maybe not the "stout defense" part. The reporter continued: "Phillips, with its quintet of rangy fast players, is easily the best lightweight team the city league has had for several years."

The deliberate style of coaching of the period, however, probably shackled the team, as the reporter's comments seem to suggest: "Perhaps if the south siders had elected to make as many points as possible they would have doubled their score, but instead they were satisfied to protect their advantage by controlling the ball most of the time." And shades of DuSable of 1954: "Phillips fouled more often than Harrison, but it was the speed of the south siders that caused them to commit a few more personals." The game's star, Al "Runt" Pullins, eventually became a Globetrotter.

The talent produced by the Phillips teams of the late 1920s gave rise to one of the great institutions of black basketball, the Harlem Globetrotters. In 1926 a semipro teams, the Savoy Big Five, was formed on the south side. In a photo of the group, from 1928, at least four of the eight players are from Phillips--Tommy Brookins (forward on the heavyweight teams of 1924 and 1925), Lester Johnson (heavyweight guard, 1924), Randolph Ramsey (heavyweight center, 1925), and Walter "Toots" Wright (heavyweight guard, 1924, 1925, 1926). William Watson of Lane was also in the photo. Not in the earliest photo of the Savoy Big Five but reportedly on the teams were two other Phillips players--Byron "Fat" Long (heavyweight forward, 1926) and William "Kid" Oliver (whose name was not found by this researcher in any box score).

In December of 1926 Abe Saperstein formed the Harlem Globetrotters from a breakaway group of the Savoy Big Five. His first team included Wright, Long, and Oliver. By 1930, his teams also included Al "Runt" Pullins (from the Phillips lightweight championship team of 1928). Notably, an early photo of the Harlem Globetrotters, from 1932, was run in the Chicago Defender with the caption "Former Phillips Stars Make Good,' with four out of the five players being ex-Phillips players-Wright, Long, Oliver, and Pullins. In later years Saperstein added other Chicago high school phenoms to his Globetrotter team, including Hillary Brown (from Crane) and Nat Clifton (from DuSable).

The first black team to win the heavyweight title was the Phillips squad of 1930, defeating Morgan Park High, 20-19, at the White City arena. According to the Tribune, the Phillips teams had been the "favorite for the title since the opening of the schedule" two months earlier. The Chicago Defender provided extensive coverage on the team. The paper had always been sensitive to possibilities of racially biased officiating, and in the Morgan Park game, the paper had a word of praise: "The officiating in Saturday's clash was the best seen in the history of Chicago prep basketball. The foul [that] Referee Martin Morley called on [the Morgan Park player] in the last few moments of play dispelled all rumors that Phillips would get a 'raw' deal." In the same piece the paper publicly asked that Amos Alonzo Stagg invite Phillips to its national interscholastic.

In 1930, the big postseason tourney in Chicago was not the state tournament, which was considered a preserve of downstate schools, but the Stagg national tournament at the University of Chicago. (A few Chicago schools participated each year in the state tourney on an individual basis, but not Phillips.) Every year in the Stagg Tourney the Public League champion was an automatic entry--automatic, that is, except in the year 1930, when the color line reared its ugly head. Morgan Park received the invitation that should have gone to Phillips. The Chicago Tribune made no mention of this injustice, but the Chicago Defender, gave it front-page treatment. The Stagg Tourney in 1930 was facing increasing resistance from educators, and many states, especially those from the North, refused to send their champions. The southern states were still eager participants, and barring Phillips was an obvious but reprehensible way to keep the tourney alive. The Defender did not fail to point this out, and concluded by saying that "the university athletic department had bowed to the will of the ex-Confederates and their offspring."

The star of the Phillips heavyweight team of 1930 was forward Agis Bray. He later played at Wilberforce University, but achieved stardom playing on various semipro teams throughout the 1930s, such as the Old Tymers and the Collegians. When Bray died in 1979, Runt Pullins recalled in the Defender: "He was an all-around athlete, but at basketball he was best. He was fast and he could shoot. He was the best of his time." Another of his peers, Simon "Dusty" Buford, asserted that during the 1930s Bray was the best athlete in the city of Chicago. By today's standards Bray was small, about 5-foot-9 and 140 pounds, but in 1930 he was a big man in more ways than one.

With Bray still at the helm and most of the starters back in 1931, the Phillips heavyweights were figured for an easy repeat for the Public League title. They dumped Bowen and scoring machine Bill Haarlow in the semifinals, 26-23, but in the title game Phillips met an insurmountable barrier--6-foot-8 center Robert Gruenig of Crane Tech. At this time the center jump was still employed after each basket, and Gruenig won every one of them. And double-teaming Gruenig did not prevent the giant from scoring 17 of Crane's 30 points. Phillips managed 22 points in a game they were never in. Gruenig went on to become one of the greatest AAU stars of the 1930s and in 1963 was elected to the Naismith National Basketball Hall of Fame.

Phillips gained a bit of consolation for their loss of the Public League title. On March 21 at Hampton, Virginia, Phillips scored a 30-14 victory over Genoa High of Bluefield, West Virginia, easily winning the championship of the National Basketball Tournament for Black High Schools.

Meanwhile, in the early 1930s the Phillips lightweights were also making their mark. The 1930 squad, which included future semipro great Simon Buford, made it to the title game, but lost to Calumet. The 1931 team was ousted in the semifinals of the Public League championship by Englewood. The following year, however, the Phillips lights took the title game with a win over Crane Tech. They then competed in Morton High's postseason tourney of top northern Illinois lightweight teams, and in the title game lost to Morton, the perennial Suburban League powerhouse.

The tremendous success of the Phillips teams of the 1930s spilled over to fuel the success of the basketball team of Xavier University in New Orleans. From 1935-38 the squad produced a record of 67 wins and 2 losses, and at one point all five starters were from Phillips. Two of these players--Charlie Gant and William McQuitter--had been starters on the 1932 lightweight champs, and another Cleveland Bray, was the younger brother of Agis Bray. The others were Leroy Rhodes and Tilford Cole.

In the mid-1930s another black school came to the forefront in Chicago, DuSable High. In 1936, when the school was still known as New Phillips, it sent the first all-black team to play in the state tournament in Champaign (where they lost in the first round to Hull). But the DuSable story is another one, and its subsequent success in producing great teams and great athletes was paved by the Phillips teams of the 1920s and early 1930s.

Revised version posted April 1, 2005.

Published with permission. All rights are reserved by the author.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Illinois High School Association.